Welcome to Now and Again, where I’m returning to subjects I once wrote about regularly. It’s free. Subscribe!

Pull up a search window this election year, type in “examples of other electoral colleges,” and you’ll see cases that are not at all like “the” electoral college.

Possibly it’s interesting that this or that country invests executive power in a prime minister while tasking an assembly or parliament with electing a ceremonial president. Maybe it’s notable that up through the 1810s or 1820s a few state legislatures held onto their power to elect the governor. Technically, those too are electoral colleges.

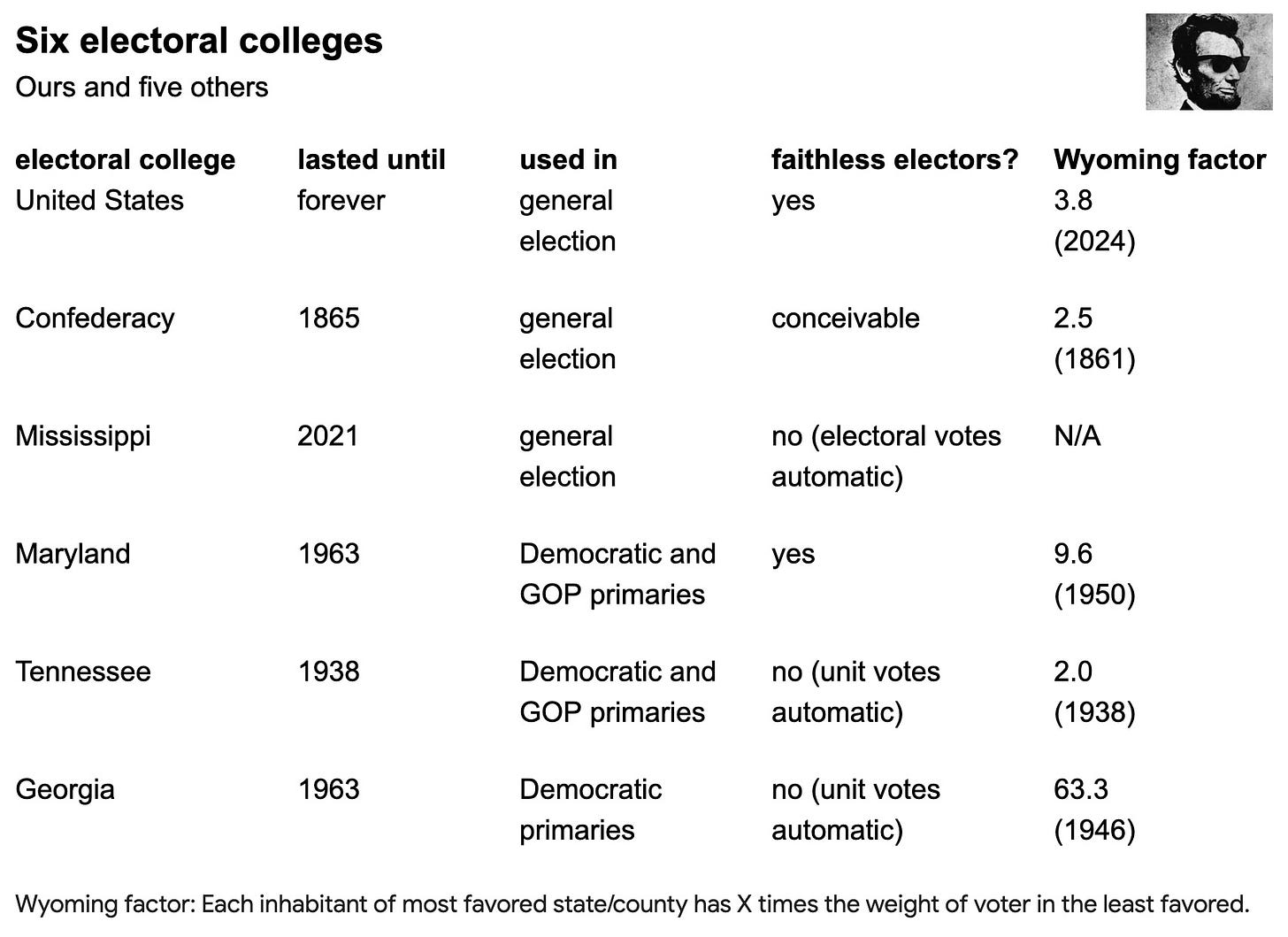

Nevertheless, search results like these are missing out on a more applicable and interesting history. Over the past 235 years, at least six real electoral colleges have emerged right here stateside. One is our federal electoral college.

The other five rose and fell more or less as follows….

Confederacy

While the Confederate constitution limited its president to a single six-year term, the method for electing that individual tracked our electoral college in every respect. Even the procedure for elections where no candidate receives a majority of electoral votes (with the House of Representatives determining the winner on a one-state, one-vote basis) was lifted whole from the 73-year-old federal constitution. Madison himself came to regret this portion of the text by the 1820s at the latest. The Confederacy kept it as is.

A provisional congress named Jefferson Davis president in February 1861 until such time as an election could be held. Davis ran unopposed that November and received the unanimous vote of the Confederate electoral college.

Electors were chosen by voters in every state except South Carolina, where the legislature performed that task just as it had in every United States presidential election since 1789. With the exception of the special case afforded by the newly admitted state of Colorado in the election of 1876, South Carolina’s 1861 vote for Davis marks the last time a state legislature chose presidential electors.

Mississippi

As a result of an avowedly Jim Crow state constitution ratified in 1890, candidates for statewide office in Mississippi faced a two-prong test. First they were required to win an outright majority of popular votes. Moreover, those candidates also had to record victories in at least 62 of Mississippi’s 122 state House districts.

In theory the state was setting a high bar for reaching the governor’s office. In practice the rule was quickly forgotten. For decades the state elected an unbroken string of Democratic governors. Then in 1999 Mississippi witnessed its first exceedingly close governor’s race in over a century.

When Democrat Ronnie Musgrove came up just shy of 50 percent in the popular vote against Republican Mike Parker, the Mississippi House of Representatives determined the winner on a one-member, one-vote basis. Musgrove was elected in January 2000 amidst negative commentary on the state’s “arcane,” “archaic,” and even “gothic” system. That criticism resurfaced in advance of the 2019 governor’s race, one that, in the end, was not as close as expected and thus did not go to the Mississippi House.

The system remained in place until 2020, when 79 percent of Mississippi voters supported Ballot Measure 2 to repeal the two-prong test. While candidates are still required to win a majority of the statewide popular vote, the 62-House-district threshold is a thing of the past.

Maryland

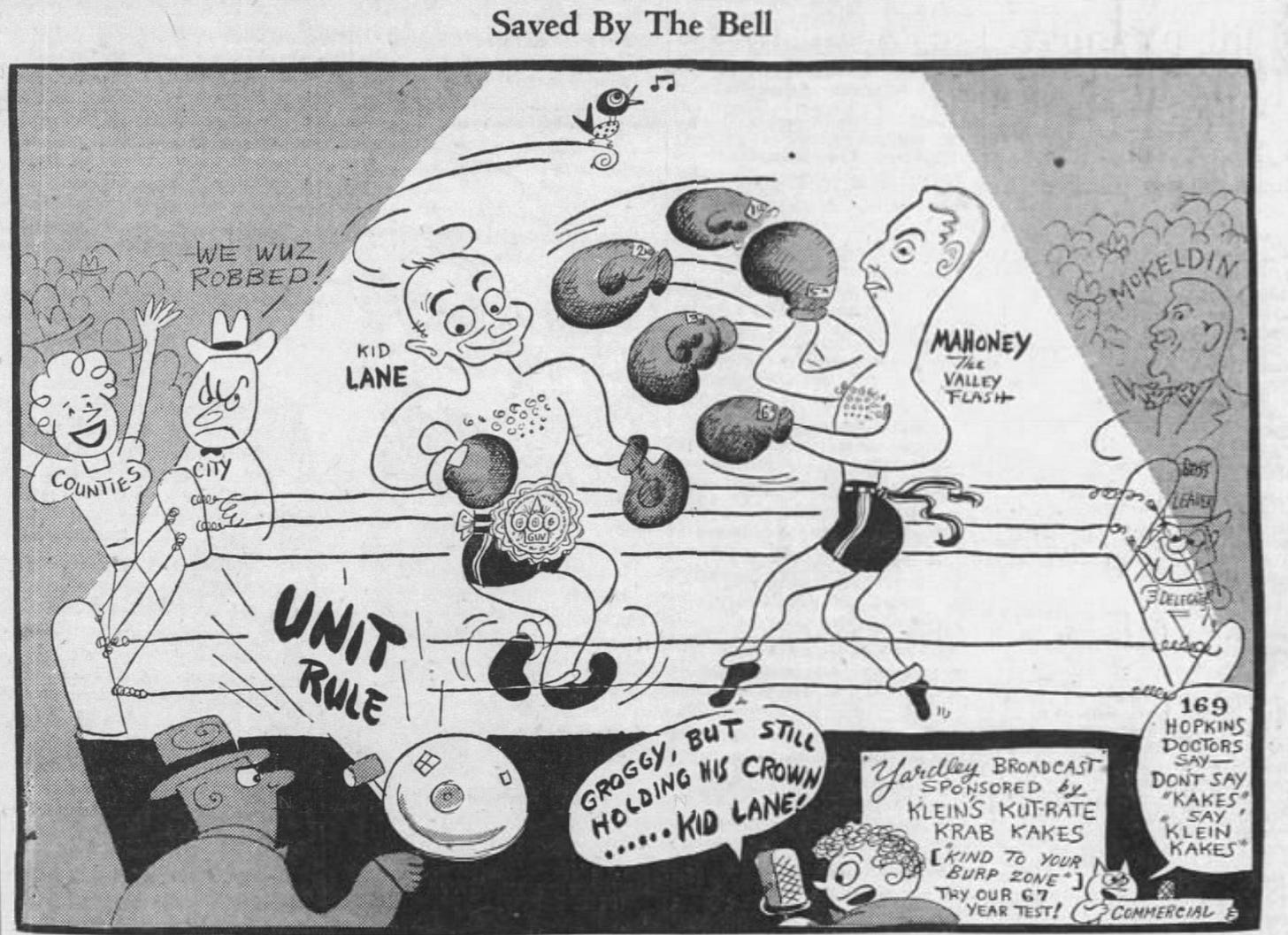

Where Mississippi’s electoral thresholds were used in general elections, Maryland’s county unit system applied to party primaries only. Counties were assigned anywhere from three to seven unit votes based on population. For its part the city of Baltimore was split into six districts and given a total of 42 votes. Nevertheless, disparities between population and unit votes produced some notably erratic outcomes.

In Maryland’s 1932 Republican primary for U.S. Senate, Linwood Clark lost the unit vote and with it the GOP nomination despite winning 58.7 percent of the popular vote. Clark’s 17 percent margin of superiority in the popular vote was so decisive he felt obligated to announce, as the Baltimore Sun put it, that “he had no plans to force his nomination for the United States Senate in the State Republican Convention.”

To this day multiple reference sites show Clark’s popular-vote total as belonging instead to the primary’s winner, Wallace Williams. A similar if less extreme inversion would occur 18 years later in Maryland’s 1950 Democratic primary for governor.

Under Maryland’s system each county was assigned a number of unit votes corresponding to its representation in the state General Assembly. A 1956 amendment to the state constitution reapportioned the Assembly, but right up until the county unit system’s court-ordered demise in 1963 it was still referred to as “a bastion of strength for the rural areas.” Maryland stands out as the one instance where a state-level electoral college nominated candidates in a consistently competitive two-party setting.

Tennessee

The Volunteer State’s unique design for a county unit system merits mention even though it existed for just four months spanning 1937 and 1938. What Tennessee’s electoral college lacked in lifespan it made up for in paradox.

The state’s novel electoral system was born of a ferocious turf battle inside a dominant Democratic party. Governor Gordon Browning was elected in 1936 with 80 percent of the vote. After failing to reach a rapprochement with longtime West Tennessee political boss E.H. Crump, Browning called a special session of the legislature in October 1937 and got his electoral college for party primaries.

On paper the county unit system curbed the power Crump was exercising in primaries through Memphis and its popular vote. Unit votes were pegged to an index of either a county’s support for the party in the previous general election or its total population, whichever was lower. In February 1938, however, the Tennessee supreme court threw out the electoral college on the grounds that a state can’t penalize a county for high turnout in general elections.

What’s noteworthy is that Browning’s self-serving and legally questionable departure from a “one person, one vote” principle had the capacity to function in such a small-d democratic manner in apportioning primary electoral votes. The governor’s system would have been based on approximately 2,500 unit votes that, by the standards of our federal electoral college, were exceedingly well calibrated to population. Compared to Tennessee’s experiment, other electoral colleges exhibited weaker correlations to population figures while surviving far longer.

Georgia

Of all the state-level electoral colleges, Georgia’s carried far and away the highest profile nationally. While Georgia’s county unit system was used only in party primaries, the Democratic party’s hold on the state was so dominant that for 70 years winning the nomination was synonymous with election to office. Prominent early- and mid-20th-century political figures from the Peach State like Gene Talmadge, Walter George, and Richard Russell all advanced to the national stage by winning what at times were highly competitive primaries within the county unit system.

Talmadge in particular focused national attention on Georgia’s peculiar electoral system. In 1946, he won a fourth term as governor by prevailing in a bitterly contested Democratic primary despite the fact that he lost the popular vote. Talmadge’s victory was a story from coast to coast that summer, marking the first time many newspaper readers encountered the idea of a candidate winning with fewer votes than the opponent. Moreover, Talmadge had based his campaign on race in a year where Georgia’s “white primary” had just been ruled unconstitutional and some 100,000 Black voters went to the polls. Talmadge declared himself “the white people’s candidate” and ran under the banner of “Let’s keep Georgia white.”

The fact that Talmadge was able to defeat his opponent in the 1946 primary was due in part to a system exhibiting an extraordinary degree of geographic imbalance. With a population of fewer than 2,500 people, Echols County possessed 63 times more weight per ballot in Georgia’s electoral college than did Atlanta’s Fulton County (population 474,000). One Georgia state legislator summarized the county unit system’s impact when he told a big-city colleague: “The situation is simply this. We’ve got the power and you haven’t, and we ain’t going to give it up.”

Fulton County in particular chafed under the state’s electoral college. Between 1946 and 1962, a series of federal lawsuits were filed on Fourteenth Amendment grounds by leading Fulton residents up to and including the founder of Emory University’s political science department (Cullen B. Gosnell) and the mayor of Atlanta (William B. Hartsfield). These efforts finally bore fruit in 1963 at the Supreme Court in Gray v. Sanders, a ruling which, in effect, also brought about the demise of Maryland’s county unit system.

“Privately glad to see it go”

Gene Talmadge was never inaugurated for a fourth term. He died in December 1946, and in 1948 his son Herman was elected governor in a special election.

In advance of a U.S. Senate run in 1956, Herman Talmadge published two works for the consideration of Georgia’s voters. The first was “You and Segregation,” a 35,000-word objection to Brown v. Board of Education in which the author maintained that the nation is a republic, not a democracy. (“Julia Ward Howe did not style her great patriotic anthem ‘The Battle Hymn of the Democracy.’”) The second was an article citing precedents dating back to England’s Mad Parliament of 1258 in celebrating Georgia’s county unit system as the “fountainhead of democratic government.”

Possibly the state legislatures of two centuries ago that elected governors or the parliamentary bodies that even now choose ceremonial presidents were and are the real electoral colleges after all. At least these are instances where deliberative bodies could, in theory, put the “collegial” in electoral college and, as originally envisaged by the framers, reach some kind of collaborative decision.

Then again “the” electoral college never worked entirely as envisaged. Even in 1789, legislators in four states (Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware) were already deferring to voters outside the chamber and allowing electorates to choose electors. Once that happens, “electoral college” refers instead to a system where ballots are translated into electoral votes.

Five bygone electoral colleges suggest that these translations by their nature hold the potential to introduce extraneous randomness. That potential can be finessed by limiting an electoral college’s degree of geographic imbalance (i.e., lowering the Wyoming factor), by considering allocation schemes other than winner-take-all, and by eliminating the possibility of faithless electors. But the specter of system-induced randomness will always remain.

One additional conclusion to draw from past-tense electoral colleges is that precious few tears were shed after they were gone. Getting rid of an electoral college-like system was one issue on which 79 percent of Mississippi voters could agree in 2020.

When Georgia’s county unit system was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1963, the Atlanta Constitution reported on the reaction at the statehouse: “Many state leaders were privately glad to see it go, especially as long as they did not have to accept the blame for its demise.”