"The most important contest in a generation"

Georgia voted for governor in a pivotal 1946 race with 21st-century flourishes

Welcome to Now and Again, where I’m returning to subjects I once wrote about regularly. It’s free. Subscribe!

“The South faces its greatest opportunity in history,” Atlanta Constitution editor and future Pulitzer Prize winner Ralph McGill wrote in the summer of 1946. “Industry and progress are coming.”

McGill captured the zeitgeist. Georgia was drawing the interest not only of “industry” but also of the national press and even political scientists.

The state boasted the nation’s youngest governor in Ellis Arnall. Under Arnall’s administration, Georgia repealed its poll tax and became the first state to lower its voting age to 18. All of the above was notable coming from a state in the Jim Crow South that in effect had been governed by one party for 70 years.

By 1946 the question was whether this rather surprising state of affairs would continue. Arnall was term limited, so an answer would be forthcoming in that year’s Democratic primary for governor. When political scientist V.O. Key published his seminal Southern Politics in State and Nation in 1949, he termed Georgia’s 1946 gubernatorial primary the region’s “most important contest in a generation.”

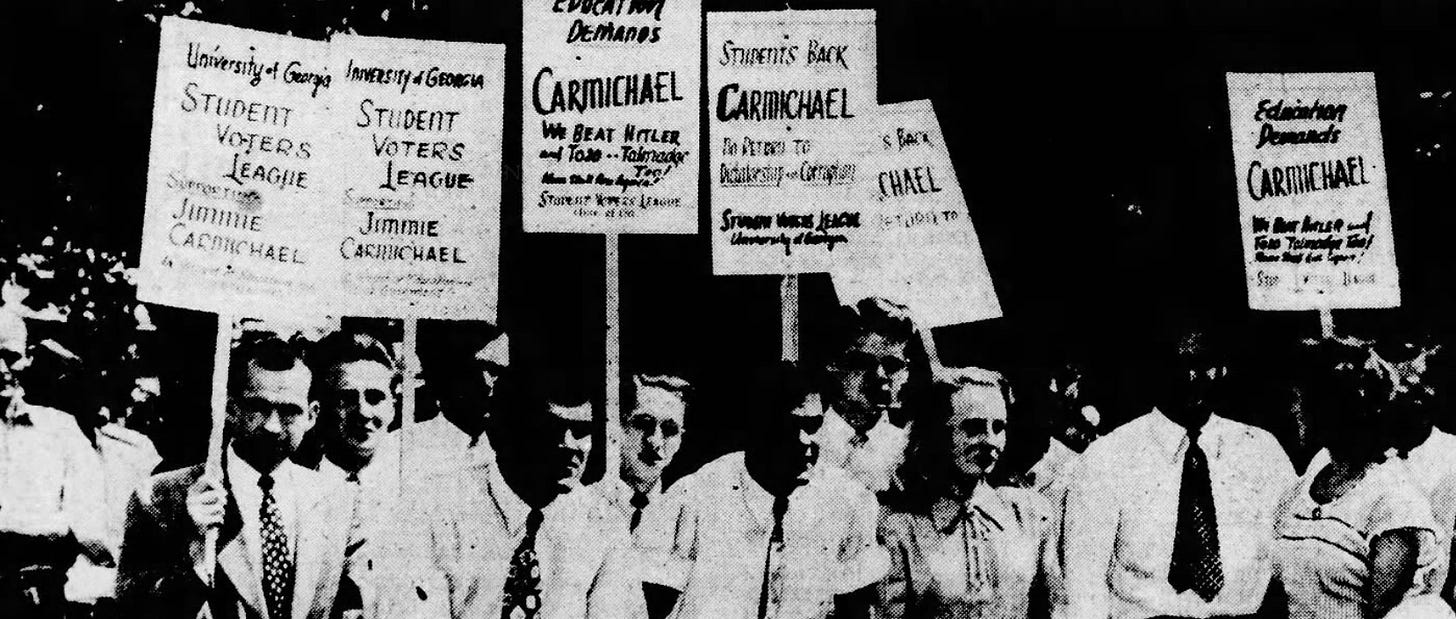

The leading candidates to succeed Arnall were James V. Carmichael and Eugene “Gene” Talmadge. Carmichael was viewed in the state Democratic party as a potential star. A 36-year-old two-term state legislator, Carmichael served as general manager of the massive Bell Bomber manufacturing plant in Marietta during the war. He was endorsed by Arnall and by an overwhelming majority of the state’s newspapers.

Conversely, Talmadge was portrayed by these same newspapers as a relic of Georgia’s past. At age 62, Talmadge had already served three terms as governor. In the 1946 campaign he was aided by Roy V. Harris, a onetime rival and former speaker of the Georgia House. Harris was renowned for his skillful maneuvering amidst Georgia’s numerous Democratic factions.

“Lacking in the elegancies”

On the stump Gene Talmadge always sported red suspenders, or “galluses.” He built suspense at rallies by arriving intentionally late, preferably in a motorcade with sirens blaring. After a few perfunctory remarks “Ol’ Gene” would yank off his suit coat dramatically to reveal the trademark “red galluses.” “The poor dirt farmer ain’t got but three friends on this earth,” he would announce. “God Almighty, Sears Roebuck, and Gene Talmadge.”

As governor from 1933 to 1937, Talmadge demonstrated a flair for circumnavigating the legislature and refashioning the bureaucracy to his liking. On multiple occasions he installed supporters (“Talmadgeites”) on oversight boards to fire any and all offending state employees. Removing the sitting board members or bureaucrats often entailed calling out the state militia to have the incumbents bodily expelled from the workplace. Talmadge reveled in the resulting coverage on the front pages and, no less, in the outrage on the editorial pages.

When Georgia sought the release of authorized transportation funds from the Roosevelt Administration in 1933, two conditions were placed on the state. First, Talmadge would have to lift his martial law decree in Atlanta. Second, the militia had to end its occupation of the state highway department’s offices. The governor complied even though he was no fan of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Talmadge incensed fellow Democrats nationwide by referring to the president as a “cripple” who couldn’t “even walk a two-by-four.”

The governor’s eventful tenure in the 1930s assured that perceptions of him were both deeply held and widely divergent long before 1946. After being physically expelled from his office by state troopers, Highway Board Chair J.W. Barnett said Talmadge exhibited “a deranged mind.”

A more positive assessment was offered by the president of the Georgia Power Company: “[Talmadge] is perhaps lacking in the elegancies, politeness, and very sensitive refinements, but he is sound and strong, determined and courageous….I am a great admirer of his.”

“Water over the dam”

After losing a Democratic primary to incumbent U.S. Senator Richard Russell and then leaving the governor’s chair in 1937, Talmadge entered a 1938 primary against Senator Walter George. It was a close race, one in which the former governor went to bed on primary night believing he had won. When Talmadge was informed otherwise the next morning, he charged that the primary had been stolen.

Talmadge called for all true Democrats to march on the party’s convention in Macon in order to halt George’s formal nomination and demand an investigation into alleged voter fraud. Friends told him he was jeopardizing his future in the party. “I ain’t gonna quit,” he said, but the convention briskly voted down his challenge. Talmadge could only write ruefully to a supporter, “We had stacks of evidence at the Macon Convention, but they refused to even look at it.”

The hope in Talmadge’s circle was that the former governor learned a lesson. “Gene,” an aide told him in 1939, “if you would not be so hasty you wouldn’t be in so much trouble all the time.” Talmadge replied, “You know what I think? I think that’s what’s got me where I am.”

He was elected to a third term as governor the following year. At a meeting of the Georgia university system’s board of regents in May 1941, Talmadge vowed to sack “any person in the university community advocating communism or racial equality.” The governor moved to fire the dean of the University of Georgia’s College of Education, Walter D. Cocking, and Marvin S. Pittman, president of what today is Georgia Southern University in Statesboro.

While Talmadge’s lieutenants combed Statesboro’s library shelves for subversive titles, UGA students circulated a petition. “We honestly state,” the document read, “that no racial equality has been taught, advocated, or practiced.” Talmadge was undeterred, installing enough allies on the board to dismiss Cocking and Pittman. In this instance, however, the governor miscalculated badly.

On December 4, 1941, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools revoked the accreditation of every state-affiliated institution for white students in Georgia, including UGA and Georgia Tech. Ellis Arnall, Georgia’s 34-year-old attorney general, saw an opportunity. He defeated Talmadge in the 1942 primary for governor by centering his campaign on UGA’s accreditation.

When Talmadge ran for governor in 1946, he dismissed the accreditation controversy as “water over the dam.” It was as close as he would come to admitting a mistake. “I’ll never admit I’m wrong, even if I am, and I’ll never apologize,” he said. “If I’ve made a mistake, I’ll ignore it and in time it’ll work itself out.”

Talmadge searched for an issue as potent as the one he handed Arnall for the 1942 race. He found one in March 1946, when the U.S. Court of Appeals affirmed in King v. Chapman that the Georgia Democratic Party’s white primary was unconstitutional.

“If I get a Negro vote, it will be an accident”

The King ruling was handed down the first week in March. By the time the Democratic primary was held on July 17 there were an estimated 135,000 Black voters registered in Georgia. “Preservation of the White Primary is not an issue in this campaign,” Arnall said. “The White Primary is gone. The courts have declared it illegal.”

Arnall’s would-be heir apparent, James V. Carmichael, said that regardless of the election’s outcome the next governor would have to follow the Court’s decision. Still, Carmichael disavowed any intention of working toward racial equality.

Talmadge warned white Georgians not to believe a word Arnall or Carmichael said. He promised to preserve the white primary and called the governor “Benedict Arnall” for betraying “the traditions which were fought for by our grandparents.”

“If I get a Negro vote, it will be an accident,” Talmadge declared, and he worked diligently to limit the chances of any such accident. “If the white citizens of the State of Georgia will wake up,” he wrote in his own weekly newspaper, “they can disqualify and mark off the voters’ lists three-fourths of the Negro vote in this state.”

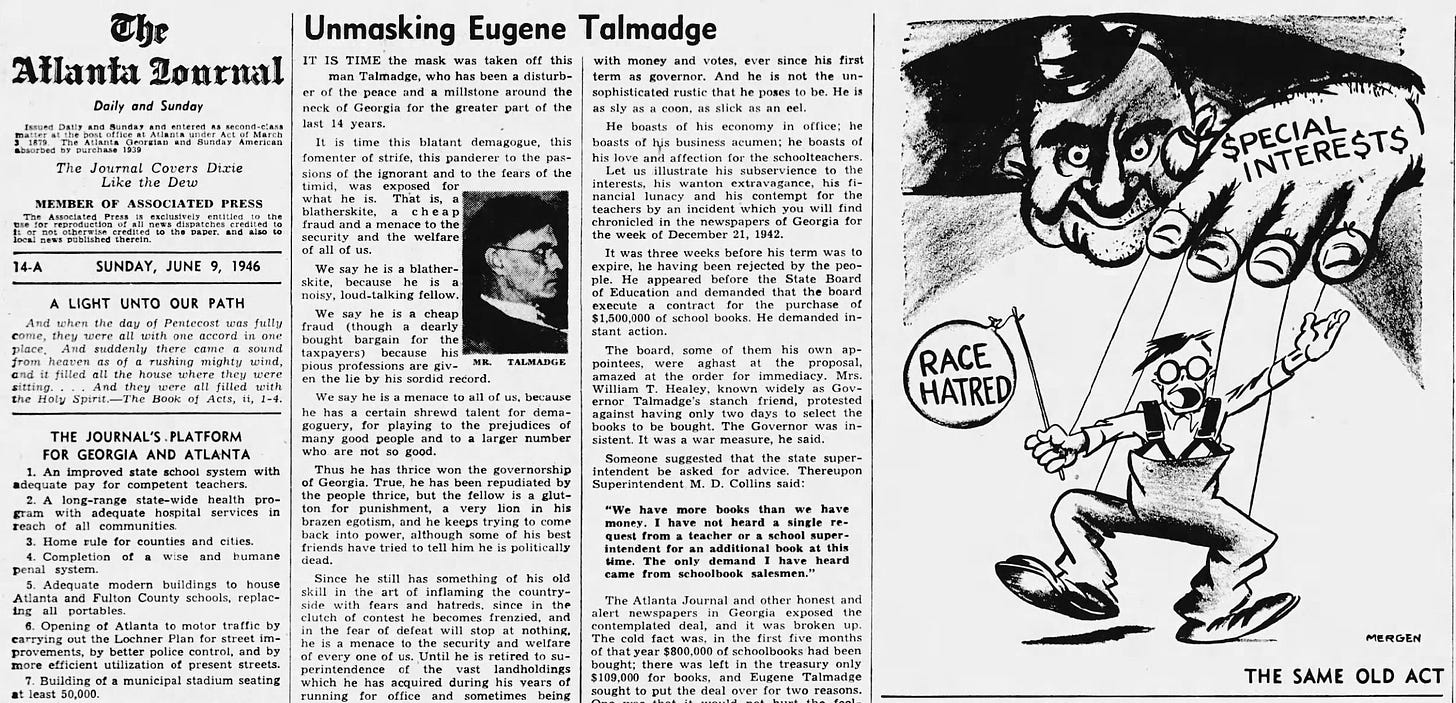

Georgia’s two most prominent newspapers, The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution, had long been critical of Talmadge. Both newspapers were particularly vocal in 1946, and Talmadge relished answering them in kind from the stump. Again and again that summer he assailed the “big-city” newspapers.

“I have told the people of Georgia that The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution have sold out to the carpetbaggers,” Talmadge reminded one crowd. “The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution are scalawags….They are not publishing the news, they are trying to make the news.”

Campaign coverage became its own campaign issue: “Talmadge, looking at Atlanta newsmen whom he had invited to sit on the stage behind him, predicted that the papers wouldn’t say between 600 and 700 persons stood in the hot sun to hear him Friday.” The former governor asserted that Atlanta was beset by violence and crimes that the Journal and the Constitution “did not dare publish.” Before the summer was out, Talmadge associate Roy V. Harris would call for “stricter libel laws” to bring about a more “responsible press.”

From rally to rally, Talmadge tailored his prophecies of what would occur if he lost. “Negro foremen will be placed in charge of white women in your mills,” he told voters in a mill town.

The weekend before the primary he warned: “Wise Negroes will stay away from the white folks’ ballot boxes on July 17.”

“This paradox could come only out of Georgia”

Once the ballots were counted into the early morning hours of the 18th, it became clear that Carmichael had outpolled Talmadge by about 16,000 votes out of some 690,000 cast, a margin of 2.4 percent. Georgia primary voters preferred Carmichael.

But Talmadge was declared the winner.

Democratic primaries for governor in Georgia weren’t decided by popular vote. Instead, the winner was determined by means of a state-level electoral college.

The county unit system, as it was called, had been in place in the state’s Democratic primaries since 1898 and in Georgia law since 1917. The Associated Press explained what happened.

Red-gallused Gene Talmadge of the unruly forelocks and the acid phrase is to be governor of Georgia again — but not by popular choice.

This paradox could come only out of Georgia….

The simple — but complicated — fact is that Talmadge won a majority of county unit votes in Wednesday’s Democratic primary, open for the first time to Negroes who voted in large numbers.

But the candidate backed by Gov. Ellis Arnall, 36-year-old James V. Carmichael, got a plurality of the 700,000-odd votes cast in the primary, the actual election in Georgia.

The Atlanta press corps speculated that Talmadge had benefited from the deep knowledge of the county unit system brought to the campaign by Harris.1 A speaker at the ensuing state convention brought the house down by declaring that the “three sweetest words in the English language are ‘county unit vote.’”

Other reactions were less celebratory. In Washington, syndicated columnist Drew Pearson called the outcome the “most alarming political development in the nation,” stating that “Talmadge, like Hitler, was elected by a minority of the voters.” The Washington Post lamented that Georgia’s “little experiment in civilization” was ending so soon.

Florida was considering a proposed amendment to the state constitution to create its own county unit system. After witnessing Talmadge’s win, however, second thoughts were voiced in the Sunshine State. A Tampa Tribune editorial stressed that “the people of Florida must be actively and earnestly on guard against” any such systems that “destroy election by the will of the people.”

Sounding a more stoic note, a Massachusetts newspaper remarked that Georgia’s experience was hardly unique. After all, presidential candidates had won elections while losing the popular vote in both 1876 and 1888. “But if it had continued to happen in the election of a President,” the Springfield Republican added, “influences would have been set at work by which the federal constitution would inevitably have been changed.”

“One of the meanest guys I ever knew”

Georgia’s county unit system was similar to the electoral college but exponentially more imbalanced geographically. In 1946 each ballot from tiny Towns County carried 127 times more weight than one cast in Atlanta’s Fulton County.

Within days of the primary, Emory University political science professor Cullen B. Gosnell filed suit in federal court. As a Fulton County resident, Gosnell claimed the county unit system denied him equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. Gosnell was represented by a former chief justice of the Georgia Supreme Court, but his suit was dismissed by a three-judge panel in Atlanta. That fall an appeal was rebuffed without a hearing by the U.S. Supreme Court.

By this time Talmadge was ailing. He was noticeably more gaunt during the 1946 campaign, and the photo used in his advertising appeared to be 10 to 15 years out of date. In the first flush of victory on primary night Talmadge spoke of the “years” taken off his life having to fight the press in this campaign. Five months after the primary he was hospitalized, and on December 21, 1946, Eugene Talmadge died before he could be sworn in for a fourth term.

Georgia’s Three Governors controversy followed. Arnall, incoming lieutenant governor M.E. Thompson, and Talmadge’s son Herman all laid claim to the office. Georgia’s high court elevated the lieutenant governor, but Talmadge’s son promptly won a special election in 1948. Herman Talmadge served as governor until 1955 before taking the place of his father’s old foe George and filling the state’s U.S. Senate seat next to Richard Russell.

Throughout the 1950s, Fulton County residents continued to follow Professor Gosnell’s example by filing suit against Georgia’s county unit system. Finally, a 1963 suit succeeded at the Supreme Court as Gray v. Sanders. In Gray, the state of Georgia argued that the U.S. Senate and the electoral college offered examples where citizens’ rights coexisted constitutionally and peacefully alongside mathematical inequalities. The Court responded, in effect, that the Senate and the electoral college are in the text of the Constitution but Georgia’s county unit system is not.

Herman Talmadge served four terms in the Senate. He was defeated in the 1980 general election by Mack Mattingly, the Senate’s first Georgia Republican since Reconstruction.

In the summer of 2019, Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden was widely criticized for naming segregationists like Herman Talmadge and Mississippi’s James Eastland as examples of “civility” among past Senate colleagues. However, Biden also referred to Herman Talmadge as “one of the meanest guys I ever knew.”

If Biden’s assessment was correct, Herman Talmadge may have inherited the trait. Gene Talmadge once said, “I’m just as mean as cat shit.”

In the late stages of the campaign Harris was often mentioned in connection with a third candidate, Eurith D. Rivers. Speculation centered on Harris and his political connections as one answer to a common question. Why did Rivers (another former governor) remain in the primary long after a statewide consensus emerged that he couldn’t win? Rivers ended up drawing almost 70,000 votes, even a fraction of which could have been valuable for Carmichael.