Welcome to Now and Again, where I’m returning to subjects I once wrote about regularly. It’s free. Subscribe!

When bedlam erupted in the House of Representatives on June 4, 1929, the cause appeared entirely unrelated to anything having to do with presidential elections. Yet the House’s resolution of one seemingly extraneous controversy would at a stroke change the outcome of a presidential race more than 70 years later.

The matter under discussion that day was the seemingly mundane question of congressional apportionment. For 120 years up to the early 20th century, the size of the House had grown along with that of the nation itself. As the country’s population increased and states were added, the House grew ever larger. Membership rose from 59 individuals in the initial seating of the First Congress in March 1789 to 435 representatives as a result of the apportionment following the 1910 census.

This trend came to an abrupt halt with the census of 1920. Throughout the ensuing decade and right up to 1929, Congress proved unable to enact a new apportionment. For the first time in the nation’s history, House membership was not updated to reflect the results of the most recent census.

Congressional delegations from rapidly growing states like California and Michigan demanded a new apportionment. Opposition came primarily from members representing the South and interior West. Their intention was not to stand in the way of a just apportionment, these representatives insisted. Instead, these members maintained that they merely sought an accurate census reflective of the American citizenry as opposed to sheer population.

“The riffraff of the Old World”

John Rankin, a Mississippi Democrat, claimed the 1920 census had counted millions of “alien interlopers” when apportionment should be based on true Americans only. “They come from the riffraff of the Old World,” Rankin said of the “interlopers.” “From them are recruited the gunmen and the gangsters.” Rankin and like-minded colleagues demanded an amendment to apportionment legislation that would exclude non-citizens from census results for the purpose of congressional representation. Their amendment passed on June 4.

Then party lines began to blur on the House floor. For 14 years, Republican Representative George Tinkham of Massachusetts had been introducing legislation to enforce Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment and reduce the House representation of any state denying Black citizens the vote. His bill had never drawn enough support to even come up for a roll-call vote.1 Now, however, a bipartisan coalition in the GOP-dominated House seized on Tinkham’s amendment to the apportionment measure as a means of answering Rankin and his allies.

Encouraged by cries on the floor of “Come on! Come on!” a hasty majority made up of Republicans and big-city Democrats found common cause in Tinkham’s perennially unsuccessful proposal. As members from the South fumed, a provision that nominally would have enforced the letter of the Fourteenth Amendment was shouted through and approved. On paper, it marked the most momentous step taken by the House on civil rights since Reconstruction. A reporter wrote that it had been “a wild afternoon,” one in which “the House ran away from its leaders.”

Those leaders had seen enough. Republican majority leader John Q. Tilson of Connecticut worked for years not only to bring the House up to date with the nation’s population but also to preserve the body’s size at exactly 435 representatives. A longtime student of parliamentary procedure, Tilson took control of the floor the next day. He maneuvered the House into stripping both the South’s preferred amendment and Tinkham’s measure from the apportionment legislation. What the House passed instead came to be known as the Permanent Apportionment Act of 1929.

In addition to pegging the size of the House at 435 members, the Apportionment Act prescribed the method for the executive branch to report a new number of representatives from each state following every census. Unless Congress put forward its own apportionment, the executive’s numbers would take effect automatically.

Congress has been apportioned in this manner ever since.

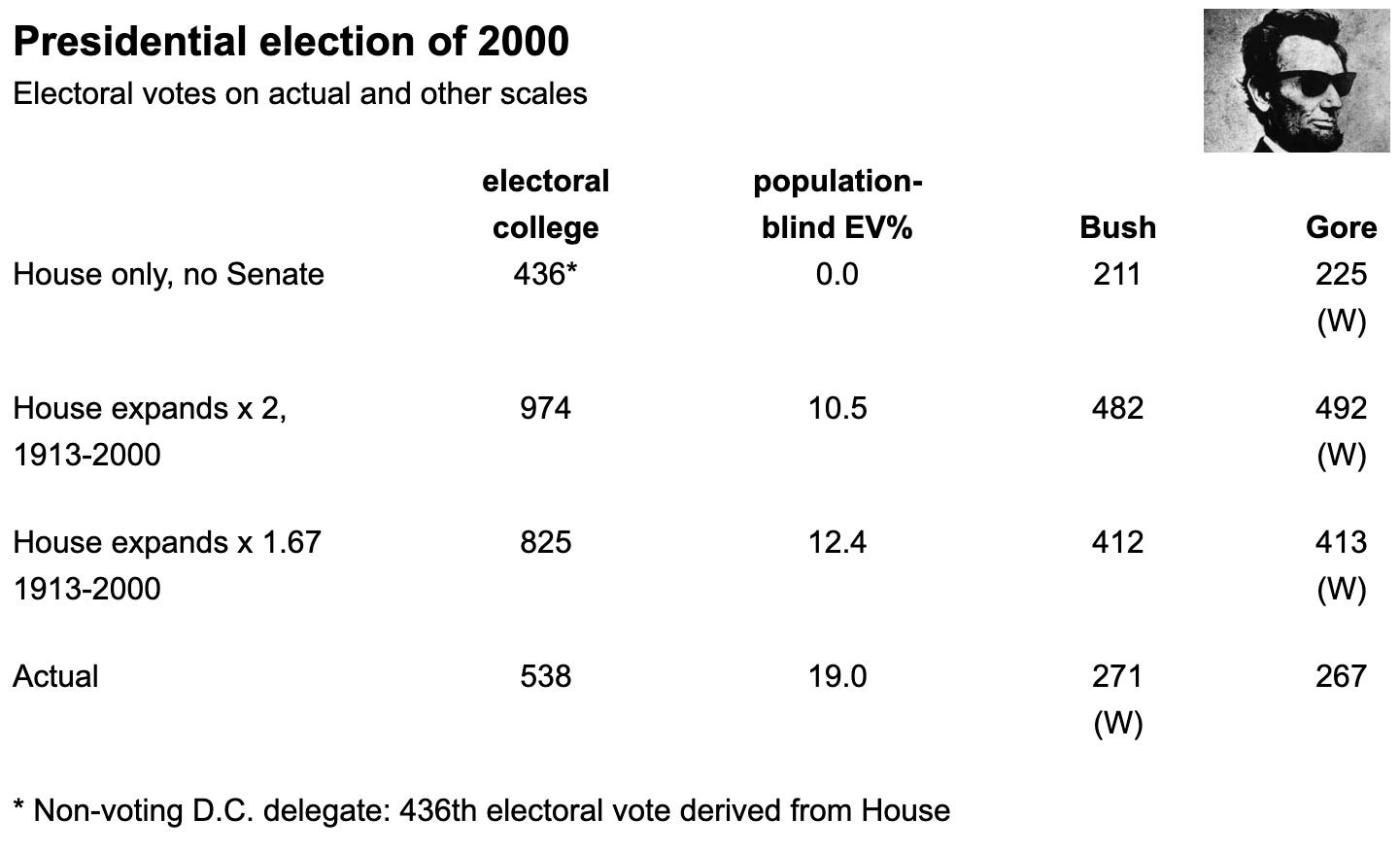

Population-blind electoral votes and 2000’s 12 percent threshold

For more than two centuries, the design handed down for presidential elections by Madison, Hamilton, and the rest of the framers has been variously celebrated, criticized, analyzed, and debated. The impact of an obscure figure like Tilson merits occasional mention as well.

The combined size of the House of Representatives and the Senate determines the number of presidential electors in the electoral college. In contests decided by an exceedingly small number of electoral votes, the sheer scale of that college can itself spell the difference between victory and defeat.

As Nate Cohn has astutely noted, Al Gore, for one, really could have used an electoral college in 2000 that was scaled on the House alone. Alternately, Gore would also have won with an electoral college derived not only from the Senate but also from a “people’s House” that continued to expand as the nation’s population more than tripled from 1913 to 2000. In either case and preserving every red and blue result from the actual 2000 map, Gore would have defeated George W. Bush even assuming a GOP win in Florida.

All presidential candidates since 1964 have competed in an electoral college where 19 percent of the electoral votes are Senate-derived and thus population-blind. In order to win in 2000, Gore needed a scale where that share instead came in at or below about 12 percent.

Certainly, zero percent would have worked….

Noting that a different scale for the electoral college would have swung the election of 2000 is in one sense purely theoretical. At no point in the nation’s history has the share of electoral college votes derived from the Senate dropped below 16 percent. Any actual electoral college scale from 1789 down through 2020 would have yielded a Gore defeat when applied to the 2000 map.

On the other hand, any House expansion occurring alongside an assumed 50-state Senate would shift this actual scale. In 1929, Congress elected to lock in the size of House at 435 until further notice.

Revisiting that decision has long been advocated on its own House-specific merits quite apart from any consideration of the electoral college. In the 21st century, each member of the U.S. House represents a significantly larger number of constituents than do office holders in the lower chamber of any other OECD legislature.

The framers after the framers

Tilson and the 71st Congress doubtless achieved something noteworthy. They removed an object of bitter congressional dispute from the political arena more or less entirely.

When an apportionment “debate” was staged in June 1929 between Rankin and Michigan Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg, their discussion was carried live coast to coast on the CBS radio network. Rankin claimed that permitting the executive branch to draft a conditional House reapportionment after each census would surrender “one of the sacred principles of legislative government for which our forebears have fought for 1,000 years.”

The Permanent Apportionment Act soon followed. Over the last 95 years, congressional apportionment has proceeded with minimal fanfare as “a purely ministerial duty” just as Tilson envisaged.

What’s notable in retrospect is that fashioning an automated apportionment process was linked to and indeed championed primarily on the basis of the not necessarily related act of capping the House at 435 members. Freezing the size of the House was cast as a civic-minded yet long delayed step toward responsible governance. In the 40 years leading up to the 1929 apportionment act, no state ever once lost a seat in the House.

The Permanent Apportionment Act changed this state of affairs dramatically. No fewer than 18 states lost seats following the 1930 census, while California alone gained nine. The newly reconfigured House remade the non-Senate-derived portion of the electoral college in its own image, though this was of little or no consequence in an era heavy on landslides in presidential elections.

Nevertheless, in creating a new and so far enduring scale for the electoral college Tilson ranks in his own right as a latter-day framer of our system for electing presidents. As seen in the 2000 election, his handiwork can even be decisive in edge cases.

“Edge cases” refers to very close finishes in the electoral college and not necessarily to similar popular-vote totals or even to other outright inversions. Take one election from a few years back, for example.

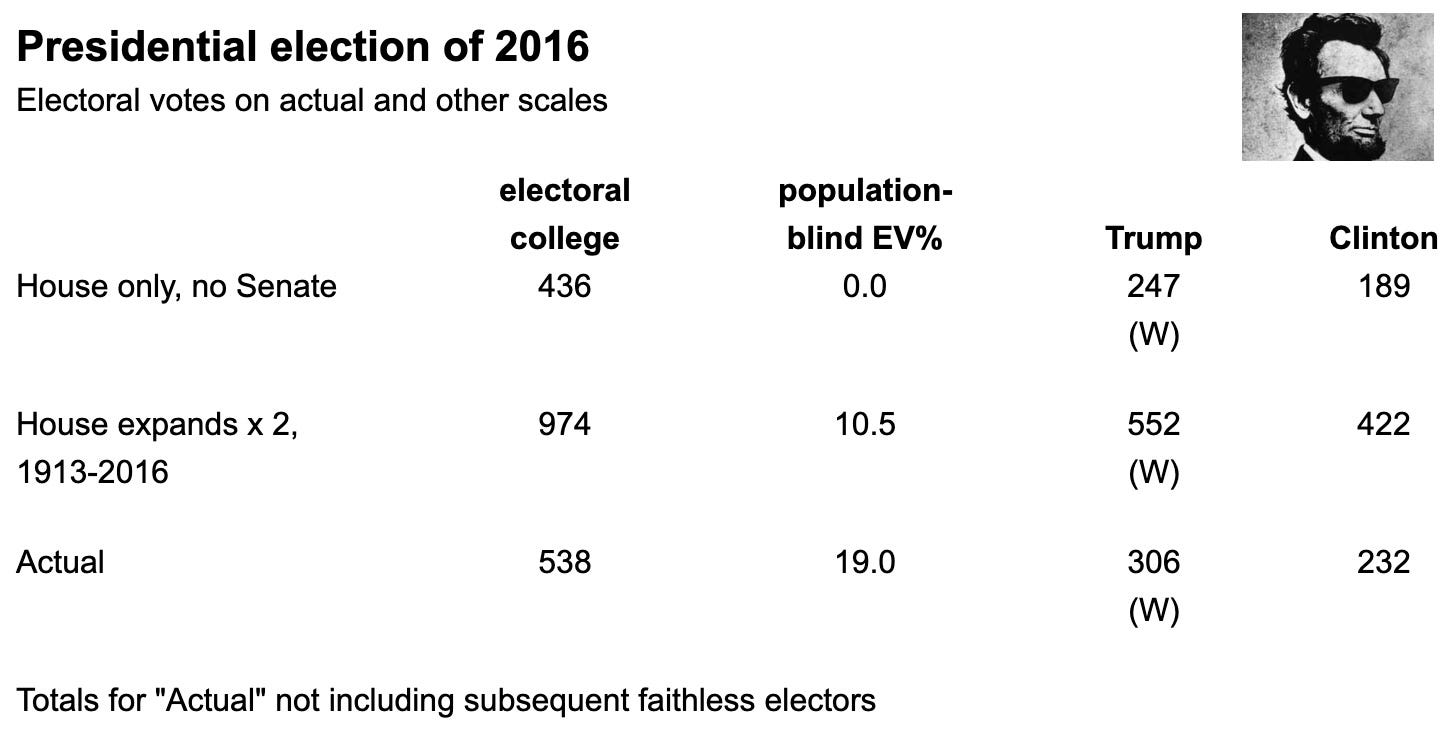

Scale meant nothing in 2016.

When a candidate outperforms their opponent 46-to-4 in electoral votes in winner-take-all states decided by popular-vote margins of one percent or less, scale will likely be an afterthought. Said candidate’s going to be difficult to beat even if they lose the national popular vote by a margin of 2.1 percent.

It turns out the state legislators who elevated winner-take-all as the electoral college’s near-universal allocation scheme between roughly 1805 and 1836 were also acting as latter-day framers. Subsequent to Philadelphia’s 1787 convention, scale and allocation emerged as gravitational fields exerting their own electoral sways through Article II.

Of these two forces, scale looms as a potential factor in only the most evenly divided electoral college results. When Gore lost to Bush by four electoral votes, scale mattered.2 The next time a similar result occurs, John Q. Tilson’s legacy could make itself felt yet again.

Across a House career spanning almost 30 years, Tinkham steadfastly refused to campaign for reelection. Rather than canvass his Boston district for votes, he frequently and pointedly embarked on long African safaris during campaign season.

Not including one subsequent faithless elector.