Mind over sample size

It's just 67 outcomes in a beautiful game

Never mind a Final Four with nothing but No. 1 seeds. We saw the same thing a mere 17 years ago. It happens all the time, relatively speaking.

No, when examining all the data from the NCAA Division I men’s tournament the single biggest takeaway is clearly the shocking collapse of Catholic basketball. This spring marks the first time in 23 years when there wasn’t one Catholic school represented among the final 16 teams.

Will someone please explain how there are books out there on the topic of “Why are Catholic schools so good at basketball?” If anything there should be books on why Mormons, public schools, and Duke are so good. There’s your 2025 men’s Sweet 16 right there.

The results are both clear and aberrant, yet no one’s asking what’s wrong with Vincentian hoops. Stephen A. isn’t berating the Association of Jesuit Colleges and Universities.

Possibly this is because “Why are Catholic schools so good at basketball” functions as a one-way narrative circuit. We ask the question when Gonzaga or Villanova or Sister Jean or whomever reaches the Final Four. When they don’t we leave the query aside and uncontroverted until the next time it’s topical.

Many of our folk narratives work in this same manner and not just for March Madness. Our tendency is quite naturally to overlook not only the dog that doesn’t bark but also the much larger seismic shifts in the background. It was but 14 years ago after all when revenue sports at the college level were being compared to slavery and colonialism. When that was addressed we moved on to complaining about one comparatively unexciting tournament where it seems like the favorites always win.

By this viewer’s entirely arbitrary standards the 2025 bracket has indeed been a relatively muted affair up to now. Such was the prevailing consensus on social media for a quiet first weekend, to the point where there was much real-time pleading of the “Please, let this finally be a good game” variety.

Then the “hey, wait a minute” point was made and taken up as a more considered alternative to the braying mob’s discontent. As one unaccustomed to membership in said mob I brayed in confusion as I realized I was seeing valid big-picture points marshaled in support of a position I didn’t really embrace. Yes, the sport itself is better than it’s ever been. We really shouldn’t look past that fact and, no, we don’t ever want to go back.

It’s just that the actual games played in this healthy sport this time around haven’t been very good. They’re not as good as they were last year and they’re not as good as they will in all likelihood be next year. We can acknowledge aleatory swerves in a thriving game, surely.

The NBA has the best players in the world, quarters instead of halves, a better shot clock, and way fewer and much shorter official reviews. They too play the occasional dull game at the next level even during the playoffs. It happens.

Even if a tournament weekend falls short of expectations the good news stays the same. With NIL and player mobility the college game is righting wrongs both large and small. Players are being afforded the opportunities they have earned but lacked for far too long. More prosaically, this new era of fairness and justice for all happens to make me blissfully happy as a viewer. I never want to see the college game miss out on another Amen Thompson.

Every time I catch part of a Houston Rockets game it rankles me to no end that we never saw a nascent NBA All-Star like the 22-year-old Thompson in March Madness. This was worse than a basketball sin, it was our basketball mistake. I regret missing out on every one of the seven lottery picks over the past five drafts who were North American products but didn’t play college ball. It didn’t need to be this way.

Of course if an exceptionally talented Thompson-level prospect for 2026 wants to play abroad or stateside for a non-college outfit that is entirely their prerogative. But now the college game at least has the ability to compete for this pool of elite 18-year-old talent both at home and overseas.

Maybe access to these players will mean that in men’s college basketball the rich will get richer. (Note however that a time traveler from 2015 would be taken aback by how blithely and unselfconsciously we group Houston and Auburn under “the rich.”) Certainly it’s natural to wonder what will happen with respect to parity across the breadth of D-I under entirely new conditions. I for one am more concerned still about holding that unruly 364-member assembly together under one umbrella in a single postseason compact. All of the above are valid questions in the era of NIL and player mobility.

What I’m less confident of is that a 67-game single-elimination bracket in a sport where a No. 16 seed won by 20 is a sufficiently supple instrument to inform our conversation on D-I’s parity. If nothing else Ken Pomeroy’s laptop must feel under-appreciated. That thing works tirelessly every November to April to slice and dice and serve up 775,000 team-possessions on a platter. Then we go and draw deep Structure of the Sport lessons from the seven where Texas Tech coughed up a hair ball against Florida and gave us a fourth No. 1 seed.

We refer to such outcomes as the epitome of “chalk.” The origins of this usage are less clear to me, at least, than explainers commonly acknowledge even if the term does date to horse racing and to odds being written on slates.1 Be that as it may, merely saying “chalk” imparts a gritty 20th-century Runyonesque flair to us 21st-century types who in fact spend a fair amount of time sitting and staring at various screens.

As for the relationship between chalk and sweeping changes in the sport, let’s call that under review. Brackets in the late aughts, for example, were consistently chalky. We witnessed the four-No. 1-seed national semifinals of 2008 with few if any of the background factors being cited as explanatory for 2025.

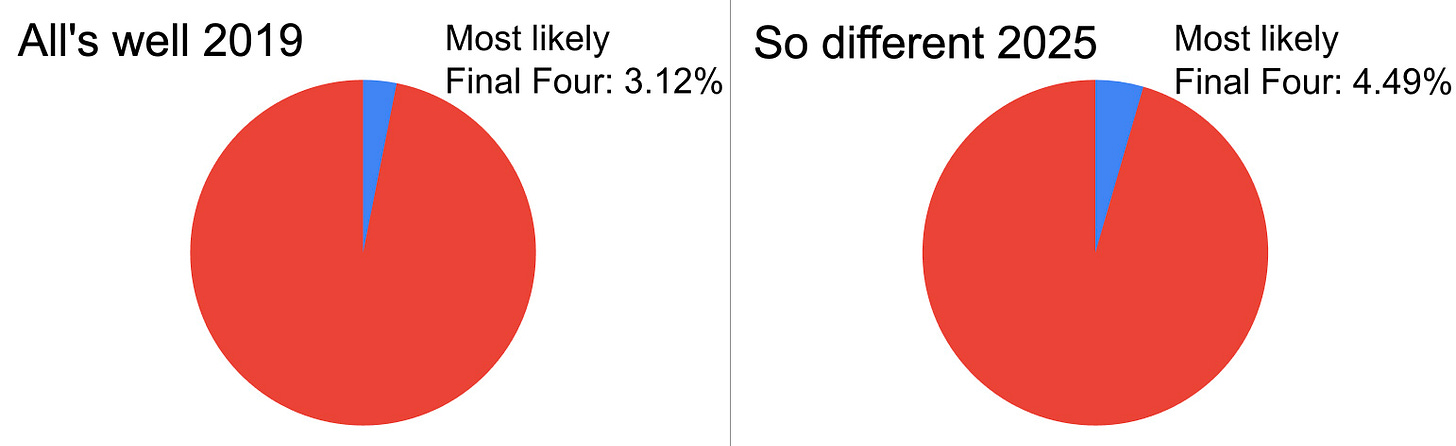

In a similar vein consider 2019, a very different time. Coaches still wore suits. The most likely group of four teams to reach the national semifinals in that pre-NIL bracket stood a three percent chance of doing so.

That probability has indeed ticked upward by 1.4 percent by 2025. Still, if we played this year’s bracket 1000 times we would likely get a different Final Four than what we have today in 950 of those tries. We also have no idea what this percentage will look like one year from now.

One guess we can hazard for the future is that if top football conferences keep expanding they will continue to set tournament records for seeds and wins as the SEC did this season. Note however that, even with all the upsets we cherish, the bracket has always favored the mighty regardless of conference affiliation. The top two seed lines alone account for 77 percent of the national titles since 1985.

Alas, if the big football conferences do come to dominate men’s basketball it will bring grim tidings for the Big-East-and-Gonzaga-centric world of Catholic hoops. That is unless Notre Dame and Boston College parlay their autonomy-conference status into becoming the next Villanova and Zags. All it takes is one exceptional tournament to set that new narrative. Never say never.