Over the last decade the most visited grave by far in Princeton, New Jersey, has been that of Aaron Burr. In addition to the usual stones and coins left as tokens, lyrics from Hamilton can be found scrawled on notes. All the while a few paces away a former president’s resting place has remained undisturbed and overlooked.

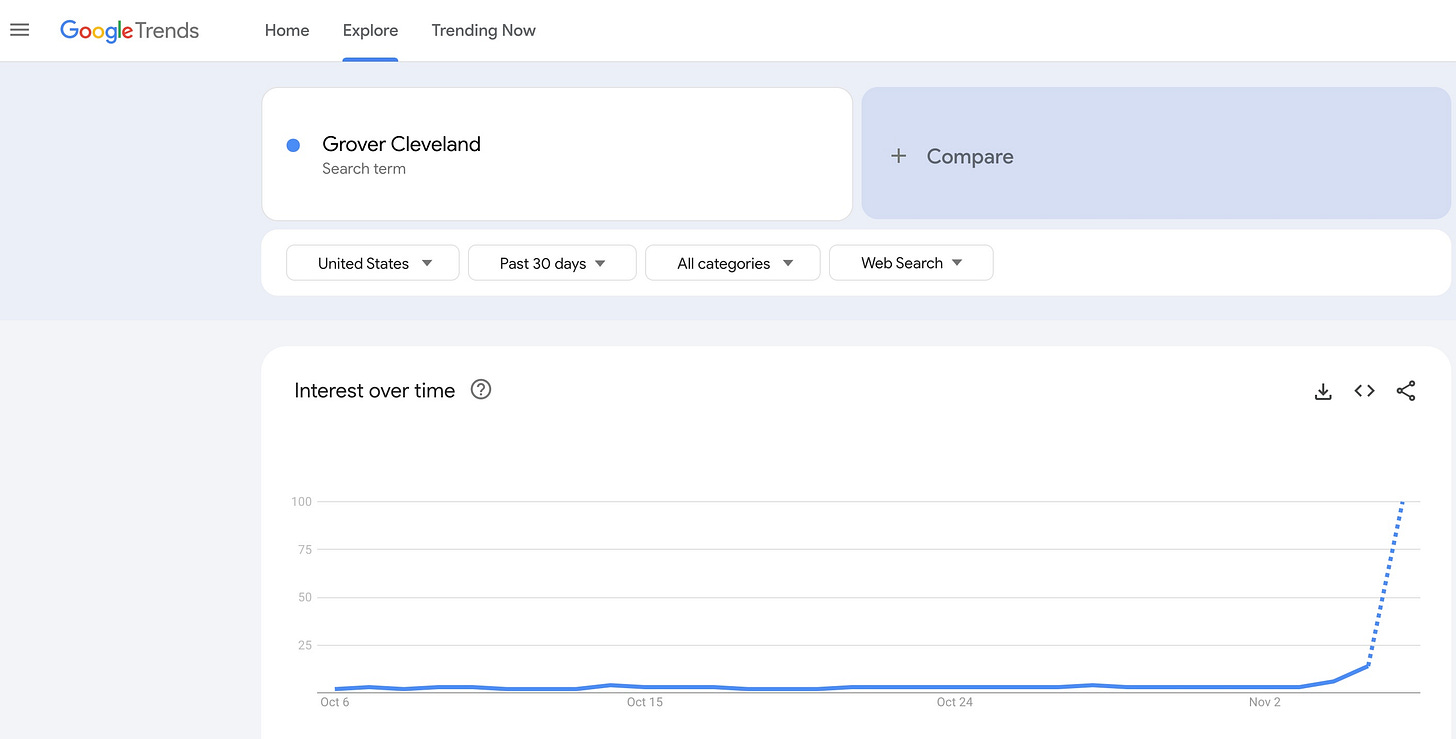

No longer. Grover Cleveland is suddenly topical.

This is what happens when a president is elected to non-consecutive terms, captures three straight nominations, secures victory in his first campaign despite a scandal concerning past sexual indiscretions, occasions a split between the electoral college and the popular vote, expends a good deal of effort on the issue of tariffs, and presides in the White House alongside a First Lady more than 20 years his junior. Plus ça change.

Presidential nominees who lose the general election don’t typically win renomination in the following campaign cycle.1 Customarily the party rids itself of a candidate that’s been tried and found wanting. This particular custom has held true 91 percent of the time since the commencement of the two-convention era in 1840.2

Then there’s the other nine percent: Grover Cleveland, William Jennings Bryan, Thomas Dewey, Adlai Stevenson, and Donald Trump. Cleveland and Trump bounced back not only to win the nomination but to capture the presidency itself.

Bouncing back is admirable, surely, but Cleveland’s story continued. He was fated to be superseded first by events, then by colleagues, and ultimately by history.

“A holy war of defense”

In the beginning Cleveland was a savior. Democrats lost six straight presidential elections before, during, and after the Civil War, often while nominating current or former governors of New York. What set Governor Cleveland apart in particular was his image in 1884 as an incorruptible figure at a particularly corrupt moment.

This time a governor from the Empire State closed the deal. Democrats regained the presidency with a dour and portly ex-mayor of Buffalo who pored over ledgers and legislative proposals line by line. Cleveland hardly cut the same figure as Democratic fire-eaters demanding repeal of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

Jefferson Davis did cut that kind of figure. The former president of the Confederacy provoked outrage in 1886 when he said the Civil War was “a holy war of defense” for the South. The New York Tribune condemned “this unrepentant old villain and Union-hater who should’ve been hanged 21 years ago.”

Davis and the Tribune alike were swimming against the tide of postwar reconciliation between whites of the North and the South. In this sense Cleveland-era debates over tariffs and free silver can appear sterile and diversionary. Why weren’t Democrats and Republicans attending to the war’s unfinished business? What was to be the legacy of Reconstruction and the postwar amendments?

The two parties did in fact battle over all of the above, the legacy question and the tariffs and the monetary policy. Cleveland supported tariffs in specific instances but saw the sum of existing duties as mere rent seeking by politically connected industries, a “vicious, inequitable, and illogical source of unnecessary taxation.” As for free silver he agreed with the overwhelming majority of Democrats from the East (to say nothing of the region’s Republicans) in seeing the cure as far worse than the disease.

Cleveland’s stated beliefs on “sectional” issues circa 1887 didn’t differ markedly from what a Republican like William McKinley would offer as president a decade later. Good wishes and pledges of fair treatment were offered to citizens of all regions and races. Black citizens were saluted for their diligence and encouraged, as McKinley would put it bluntly, to help themselves. Meanwhile Black delegates at each succeeding Republican national convention continued to affirm the paramount importance of actual voting rights as opposed to words in the Constitution.

Today, looking back at the period between the Compromise of 1877 and the turn of the century, the presidents appear boring but the questions were momentous and the outcomes were fateful.3

“This obsolete electoral college system”

As a Democrat in the White House, Cleveland was a walking symbol of postwar “national reconciliation.” He dedicated his 1887 annual message to a call for lower tariffs only to be defeated in his bid for reelection by avowed protectionist Benjamin Harrison of Indiana.

Harrison lost the popular vote but flipped New York and his home state to win the presidency. The electoral inversion drew attention not only to what a Democratic editor termed “this obsolete electoral college system” but also to the healthy majorities Democrats achieved on very low and very, very white turnout in the South. One Republican newspaper observed: “There is always sure to be a large majority where only one party is allowed to vote.”

From Cleveland there was no protest. He fancied himself as others saw him, a principled constitutional stalwart who built his reputation through vetoes as both governor and president. As it happens he also belonged to a party wherein the continued nullification of that constitution’s 15th Amendment represented the deepest commitment if not core identity of a good many colleagues. Popular-vote victor Cleveland didn’t cry fraud in the shadow of that nullification much less object to the rules of the game as set forth in Article II.

Republicans raised tariff rates to almost 50 percent under Harrison only to suffer a midterm setback of historic proportions. In what Joseph Pulitzer called the great political revolution of 1890, Democrats gained 82 House seats in a chamber of 332 members. “The public uprising against the new tariff was as much an act of petulance as of true indignation,” Allan Nevins wrote in his 1933 Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Cleveland, “as much a demonstration against the increased prices attributed to the law as against its principle.”

Harrison’s other priority on Capitol Hill was a voting rights act known as the Lodge Bill or, more pejoratively, the Force Bill. In his first annual message the president called for Congress to act on voting rights “within its well defined constitutional powers.” The call was answered by Henry Cabot Lodge, rising Republican star and ally of the even younger Theodore Roosevelt. The representative from Boston proposed extending congressional oversight to elections for the House of Representatives.

“The white people of Mississippi will control the affairs of this state”

Mississippi immediately called a convention for a new state constitution to preserve the status quo at the ballot box. Kansas Senator John J. Ingalls took to quoting Mississippi newspapers at length in floor debate to prove that the state’s new constitution was being drafted expressly to prevent Black citizens from voting. The Jackson Clarion-Ledger responded to the Republican directly: “The white people of Mississippi will control the affairs of the state. Mr. Ingalls can quote this in his next speech.”

In the end Democrats bargained with GOP senators from the West and offered their support for a silver purchase act in exchange for blocking the Lodge Bill. A Republican senator from Colorado asserted that there were “many things more important and vital to the welfare of the of this nation than that the colored citizens of the South shall vote.” Lodge’s bill met its demise in January 1891.

The Harrison administration’s failure on voting rights marked an instance where Democrats refused to accept victory. At Cooper Union in the fall of 1891 Cleveland said the nation had just witnessed Republicans “planning to retain partisan ascendancy by throttling and destroying the freedom and integrity of the suffrage through the most radical and reckless legislation.” He then campaigned on the Lodge Bill in 1892. “I regard it as a most atrocious measure,” he wrote in a public letter that summer, “and I do not see how any Democrat can think otherwise.”

Democrats did not think otherwise. Over an entire generation, from 1866 to 1890, no representative or senator elected as a Democrat cast a single vote in support of a voting rights or civil rights measure before Congress.

The furor over what Democrats called the Force Bill served to obscure a novel political development. Cleveland was a leading candidate for the 1892 nomination despite losing to Harrison in 1888. The former president had after all won the popular vote twice, a feat no Democrat since Andrew Jackson (three times) could match. Facing what they believed would be yet another New York-centric electoral college map, Democrats turned to Cleveland once again.4

It worked. Cleveland defeated Harrison by the then unheard of popular-vote margin of three percentage points. The election of 1892 was the first race in 16 years decided by a popular-vote margin greater than one percent.

Cleveland, Bryan, Tillman, Wilson

Democrats would not win another presidential election for two decades. The impact of the Panic of 1893 would prove as profound for the party as it was devastating for Cleveland. By chance the president’s legacy was neatly encapsulated by two Democrats who spoke one after the other at the party’s 1896 convention.

One was William Jennings Bryan. His “Cross of Gold” speech wrested the party away from its Cleveland wing and made silver Democratic doctrine. Bryan would earn three presidential nominations in his own right, losing twice to McKinley and once to William Howard Taft.

Bryan was preceded on the dais by Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina. Senator Tillman dissented from Cleveland on style as strongly as the Great Commoner did on silver. In his first speech in the Senate, Tillman labeled President Cleveland a “besotted tyrant.” The senator was already known for having referred to the president as “bag of beef” and for saying he wanted to poke him with a pitchfork. South Carolina newspapers pleaded with Tillman to tone down his rhetoric, but his supporters loved it. They called him Pitchfork Ben and sported tiny replica pitchforks on their lapels.

Cleveland exited the White House and retired to Princeton, New Jersey. As of 1902 Princeton University’s president was Woodrow Wilson. Soon the only Democratic presidents between James Buchanan and Franklin Roosevelt were on opposite sides of a surprisingly bitter local controversy attracting national attention. Wilson wanted to reorganize the university according to his “Quad Plan.” Cleveland opposed the plan as a member of the board of trustees. Princeton stayed un-reorganized.

Wilson bid adieu to campus politics and relocated first to New Jersey’s governor’s mansion and then the White House. In 1913 Tillman eagerly partnered with the new president to, in the words of Stephen Kantrowitz, “reduce the number of black federal employees, strip them of authority over whites, and segregate those who remained.”

“Bourbon Democrat” was a favorite epithet hurled by Tillman. The term originated with the Bourbons restored to the French throne after Napoleon’s fall. Talleyrand reputedly remarked that during their exile the royals had learned nothing and forgotten nothing.

By this definition Cleveland was no Bourbon. During his four years out of office he seems to have savored the pleasures of a growing family. He likely returned to the White House with nothing that needed to be forgotten and no scores to settle. Cleveland’s graveyard neighbor Burr could not have said as much.

Grover Cleveland wasn’t a Bourbon but he was every inch the Bourbon Democrat. He championed hard currency, fought for low tariffs, and acquiesced in mass disfranchisement. Regrettably the convictions were more controversial in their day than the compliance.

Henry Clay and Richard Nixon won second nominations after losing general elections and sitting out at least one cycle.

From the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804 to the dawn of the two-convention era in 1840, losing candidates won renomination in the following cycle on two occasions. Charles Cotesworth Pinckney ran against Thomas Jefferson in 1804 and James Madison in 1808. Andrew Jackson won the popular vote on a crowded ballot in 1824 only to see the House of Representatives elect John Quincy Adams. The field in the nascent Democratic party was then cleared for Jackson’s winning campaign against Adams in 1828. Democrats held their first national convention in 1832. Whigs followed suit eight years later.

The press did not find Cleveland and Harrison boring. In the campaign of 1884 Cleveland acknowledged having fathered a child out of wedlock years earlier. At age 49 he married 21-year-old Frances Folsom in what remains the only White House wedding in which a president has tied the knot. Four years after Harrison’s wife passed away in 1892, the former president wed his late wife’s niece Mary Lord Dimmick. Months prior to the wedding Harrison’s adult children went public with their opposition to the marriage. The family dispute hit front pages on both sides of the burgeoning circulation war between Pulitzer (“SHE RULED THE PRESIDENT”) and Hearst (“MRS. DIMMICK IS HARRISON’S RULER”).

It’s no disservice to Cleveland to note that a party that nominated just three different candidates from 1884 through 1908 despite winning just twice in seven outings may not have had the deepest national bench. The Civil War cast a long electoral shadow.