British historian Norman Davies penned a sentence that doubles as a recap of every close election ever: “I have come to hold that Causality is not composed exclusively of determinist, individualist, or random elements, but from a combination of all three.”

In the United States our distinctive method for electing presidents perhaps leads us to give the random elements short descriptive shrift. An indirect system centered on an electoral college where 98 percent of votes are winner-take-all offers an ideal crucible for randomness.

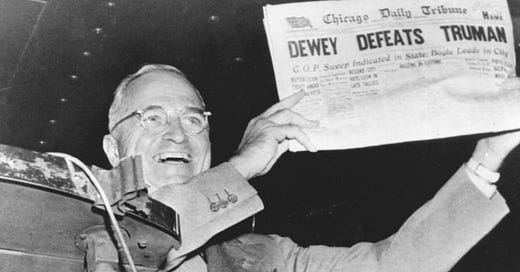

Take 1948. While President Harry Truman’s surprise victory over Republican nominee Thomas Dewey looked decisive enough in the electoral college, the outcome was in truth historically volatile. In the general election Truman was flanked by Democratic apostates to both his left (Progressive Party candidate Henry Wallace) and right (States’ Rights Party or “Dixiecrat” nominee Strom Thurmond).

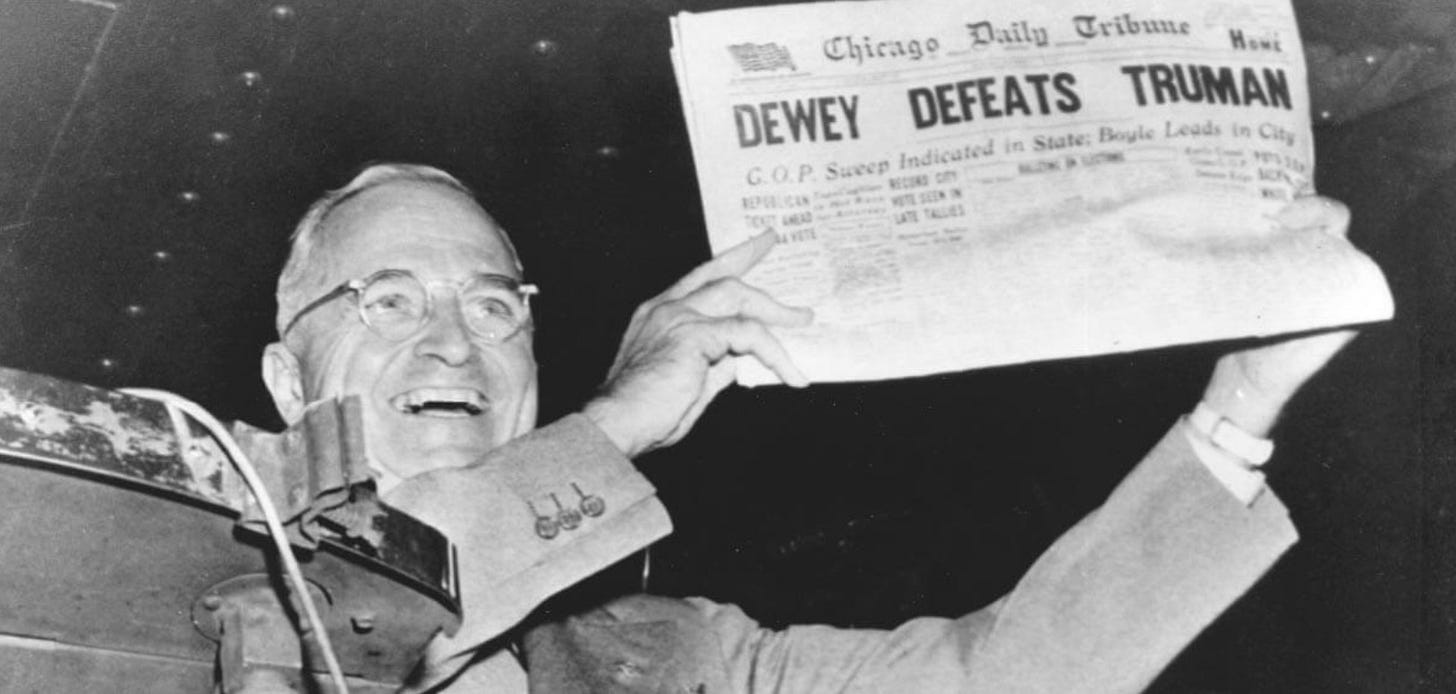

The president was fortunate the election wasn’t thrown into the House. A swing of 25,000 votes in California and Ohio would have resulted in the nation’s first contingent election since 1824.

With three different candidates winning multiple states and a fourth making a critical difference in the electoral college’s largest prize, 1948 captured our system’s idiosyncrasies in rich detail. Truman didn’t catch every break, but random twists that prognosticators couldn’t foresee did favor the president more often than not.

Consider four aleatory bounces that clearly went Truman’s way:

1. The random incident behind Dewey’s “avalanche of lethargy”

One November ritual that’s largely gone missing since 2016 is the vituperative postmortem from within the losing party. When partisans acknowledge having lost, intra-party critiques can be savage.

A classic of the genre was offered by a Republican operative in 1948 after Dewey, the sitting governor of New York, suffered his stinging defeat: “Dewey’s campaign was smug, arrogant, stupid, and supercilious….It was a contemptuous campaign, contemptuous alike to our antagonists and to our friends. The Albany group proved themselves to be geniuses in the art of stirring up an avalanche of lethargy.”

Naturally, Dewey was responsible for his 1948 campaign and any mistakes can be assigned to his individualist hand alone. But by Dewey’s own lights the motivation behind what he meant to be a dignified campaign stemmed from one chance occurrence when he ran against President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In the fall of 1944, a Republican in Congress inquired about rumors that the globetrotting president left his dog Fala behind on an Aleutian island and ordered a Navy destroyer to retrieve his pet. FDR responded with a straight face and deft comic timing in what forever after was known as “the Fala speech.”

Dewey was angered by FDR’s remarks. In a portion of the speech overshadowed by the Fala section, the president accused “the opposition” of employing “the propaganda technique invented by the dictators abroad.” In Dewey’s eyes, FDR broke a bipartisan agreement on how the nominees would campaign in wartime.

Now the gloves were off, the GOP nominee said two nights later in Oklahoma City. FDR’s “sad record of failing to prepare the defenses of this country for war” was fair game. The president’s record was in fact “desperately bad.”

By 21st-century standards it was all very tame. Nevertheless, Dewey came to doubt the effectiveness of questioning a commander in chief’s judgment at a moment when voters believed the war’s outlook had never appeared more promising. “That’s the worst speech I ever made,” he later said, and his wife Frances agreed. At the outset of the 1948 campaign Dewey vowed that this time would be different. There would be no repeat of Oklahoma City.

Dewey envisioned a substantive campaign. What followed was instead seen by Republicans as an avalanche of lethargy, one that provided an opening for Truman’s far more energetic efforts.

2. The Democratic bosses who gave Hubert Humphrey a green light on civil rights

Central to the story that’s come down to us about Truman’s victory are the gains his party made with Black voters. A memo drafted by the president’s aides in November 1947 underscored the importance Black voters in the North and in California would likely hold in the coming election. The memo recommended that Truman make a clean break from 120 years of Democratic Party history and actively pursue those voters.

Truman delivered a special message on civil rights to Congress in February, whereupon a good many southern Democrats threatened to abandon the party in the fall election. The president then fell silent on the matter. (Granted, the silence coincided with a Soviet-engineered coup in Czechoslovakia, congressional passage of the Marshall Plan, official recognition of the new nation of Israel, and the beginnings of the Berlin Airlift.) Truman had a civil rights proposal but he wasn’t about to unilaterally write off a solid South that FDR won with ease four times in a row.

A youthful wing of the party that included 37-year-old Minneapolis Mayor Hubert Humphrey envisioned a different path to victory. Humphrey sought a plank in the party platform that matched the recommendations made by the president’s own commission on civil rights.

Truman stayed far away from any push for a stronger plank. Wrong fight, wrong time, the president’s aides told him. Privately Truman referred to Humphrey and his colleagues as “crackpots.” But Humphrey took the fight to the convention floor, calling on the party “to get out of the shadow of states’ rights and to walk forthrightly into the bright sunshine of human rights.”

Moments before he addressed the convention, Humphrey won the support of several key party bosses. “You kids are right,” New York’s Ed Flynn told him at the back of the speaker’s platform. “This is the only way we can win this election — stir up the minorities.” Humphrey’s plank was adopted. A few southern delegates, small in number initially but no less visible, walked out of the convention. One question that lingered, however, was exactly what Flynn meant by “this election.” He didn’t necessarily mean the presidential election.

Party stalwarts like Flynn, Jersey City’s Frank Hague, Pennsylvania’s David Lawrence, and Chicago’s Jacob Arvey fully expected Truman to lose. The bosses focused their efforts down-ballot instead. One correspondent reporting on the convention noted that “big city machines…realize they must hold the Negro vote if their state and local tickets are not to go down in defeat in the prospective Republican landslide this November.”

In late 1947 Truman’s aides had prioritized Black voters in the mistaken belief that the party could do so while still holding the South. Eight months later party bosses from the North prioritized Black voters in the belief that doing so would help their down-ballot candidates regardless of the consequences to the top of the ticket.

Ironically, those consequences netted out as benefiting Truman. Barely.

3. The governor-elect who ran on white supremacy but backed Truman

From Reconstruction through World War II, the Deep South voted at the national level as though it were a single political entity. In every presidential election without fail, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and South Carolina all backed the Democratic nominee.

That run came to an emphatic end in 1948, though not at all in the fashion political observers expected. The Dixiecrats ran an all-Deep-South ticket, with Strom Thurmond of South Carolina and Fielding Wright of Mississippi. To many it was a foregone conclusion that the entire region would once again unite, only this time in support of the Dixiecrats.

This assumption was strengthened in September when Herman Talmadge won Georgia’s Democratic gubernatorial primary. In a state where winning the Democratic primary was equivalent to being elected, Talmadge attacked Truman’s stance on civil rights, championed white supremacy, and received an official endorsement from the Ku Klux Klan. Talmadge wouldn’t take office until after the November election, but no decision touching on ballot access for Truman, much less on the state’s 12 precious presidential electors, could be reached without the governor-elect’s approval.

In short order Talmadge backed Truman, the very man he’d spent his campaign vilifying. Like the political bosses of the North, Talmadge fully expected Truman to lose.

An ambitious 35-year-old with big plans, Talmadge calculated that by 1950 he’d be well positioned to challenge incumbent Walter George for his seat in the U.S. Senate. By then Democrats everywhere would be uniting against President Dewey and the Republicans. When that moment came, Talmadge would campaign as the most prominent son of the Deep South who stayed true to the Democrats in 1948.

Everyone except Harry Truman was wrong about 1948, but Talmadge’s vision of reaching the Senate came to pass eventually. He chose not to run in 1950 and instead took his seat in the upper chamber in 1957 after George retired.

4. The Illinois Republicans who gave Truman a crucial lift

Henry Wallace was by turns an agronomist, cabinet member under Presidents Roosevelt (Agriculture) and Truman (Commerce), vice president of the United States, titular editor of The New Republic, third-party presidential candidate, accused communist sympathizer, and prominent capitalist who netted (today’s equivalent of) millions in dividends from the hybrid seed corn company he founded (Pioneer).

When Wallace announced his presidential candidacy on December 29, 1947, the conventional wisdom was he’d be lucky to appear on the ballot in 15 states. Instead, Wallace qualified in 45. While the former VP received just two percent of the vote nationally, he arguably cost Truman a victory in New York.

Truman did, however, eke out the win in Illinois, where Wallace’s absence from the ballot was a significant and possibly even decisive advantage for the president. Strangely, the fact that Wallace wasn’t on the Illinois ballot ran contrary to the wishes of the Republican administration of the state. In fact the governor and state attorney general went so far as to support Wallace’s appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Even the Republican state certifying board had approved Wallace’s inclusion on the ballot. Far from being nonpartisan or high-minded, the Cook County Republicans who sat on the certifying board simply expected, with good reason, that Wallace would draw votes away from Truman.

Republicans in downstate Illinois took a different view. The downstate GOP accounted for the majority of members on what was and still is called the state officers electoral board. These professional Republicans from central and southern Illinois fully expected Truman to lose. The electoral board ruled enough voter signatures on Wallace’s nominating petitions invalid to keep the former VP off the ballot.

Illinois by no means had the toughest ballot requirements nationally, and Chicago was expected to be a key source of votes for Wallace. Protesting the electoral board’s decision in court and in public, Wallace drew a crowd of 19,000 at Wrigley Field. Such attendance figures were particularly impressive coming from a campaign that shattered norms in both the electoral and progressive traditions by charging gate admission at rallies.

Wallace raised funds successfully in Illinois, but he wasn’t on the ballot. Truman defeated Dewey in Illinois by 34,000 votes out of four million cast.

Giving them hell

Truman ran an outstanding campaign in 1948. He largely looked past a popular opponent who agreed with him on many important issues and instead worked tirelessly to portray the Republican Congress as risky. His attention to detail on issues as arcane as Department of Agriculture policies on grain storage powered wins in farm states like Iowa that even FDR lost to Dewey. The president deserves the lion’s share of the credit for his victory.

Additionally, random elements in general and being written off as a lost cause in particular played their own roles as Truman made Election Day history.