Octobers in 21st-century years divisible by four tend to be times of uncertainty. An exception perhaps proved the rule eight years ago, when the month in question was instead suffused with what turned out to be badly misplaced certainty.

In 2024, the uncertainty feels both pervasive and hard-earned. Nate Cohn is presenting data from swing states in table form with columns for “if the polls miss like they did in 2020” and “in 2022.” When column titles constitute their own cautionary evidence, uncertainty is understandable. We may well look back on 2024 and say it was close.

There are at least three distinct fashions in which presidential elections are spoken of after the fact as having been “close.” This sense that the result could easily have gone either way can then be enhanced greatly by still another variable. Something as random and arbitrary as the number and sheer cumulative size of winner-take-all states where the election was closely contested also merits attention. Call this fourth factor the outcome’s volatility.

Electoral votes and systemic conflict

Electoral votes are a singular metric. The singularity stems in part from decisions made by the framers, though, to an extent that’s customarily overlooked, it’s also the result of actions taken in the 19th and 20th centuries by latter-day framers.

While the candidate with the most electoral votes has won 49 times in a row, strictly speaking it’s not the case that by rule the candidate with the most electoral votes wins. (Ask the docent at The Hermitage about Andrew Jackson and 1824.) Instead, elections are zero-sum contests where the object is to amass a majority of electoral votes.

Six closest elections by electoral vote, 1868-2020

1. 1876: Hayes defeats Tilden, 185-184

2. 2000: Bush defeats Gore, 271-267

3. 1916: Wilson defeats Hughes, 277-254

4. 1884: Cleveland defeats Blaine, 219-192

5. 2004: Bush defeats Kerry, 286-251

6. 1976: Carter defeats Ford, 297-240

One conclusion to be drawn from this top six is that, Hayes-Tilden notwithstanding, electoral votes in winner-take-all settings tend to produce outcomes that aren’t all that close to the naked eye. Celebrations of this tendency as a hard-wired systemic virtue peaked in the late 20th century after vanishingly thin popular-vote margins in 1960 and 1968 translated into clear electoral college victories for John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, respectively.

Then again a glass-half-empty narration of this same top six could suggest that, in the instances when they do occur, close electoral college results by their nature produce conflicts that are especially fraught. In 1916 even a figure as dutiful and straight-laced as future Supreme Court Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes bided his time for two tense weeks before conceding. The concession “was a little moth-eaten when it got here,” President Woodrow Wilson told his family, “but quite legible.”

In February 1877 President Ulysses S. Grant spent the waning days of his second term, in one historian’s words, making contingency plans to take “military possession” of New York City. Following the disputed election of 1876, rumors swirled that Democratic nominee Samuel J. Tilden intended to hold his own inauguration ceremony in Manhattan at the same moment that Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was taking the oath of office in Washington.

Grant was determined to prevent a “rival” inauguration even if it meant cutting off New York’s food and water. The rumors proved unfounded, though Hayes was likely discomfited to be sworn in just hours after defiant House Democrats passed a resolution proclaiming Tilden the “duly elected President.”

Seen in this light, the turmoil of November-December 2000 was more of the same. If anything, the fact that this particular turmoil produced what was intended as a legislative remedy in the Help America Vote Act of 2002 underscores the likelihood that newer and better remedies are always required to counter the irrepressible conflicts of close elections. Turmoil has continued after HAVA.

Popular votes and democratic lessons from an undemocratic era

The closest presidential elections by popular vote can be tidily summarized in reverse chronological order. In the recent past there is the electoral inversion of 2000. Past that are two very close races from the 1960s. The rest of the top six is made up of three consecutive elections from the 1880s. On paper the national popular vote in 1880 was closer than any one state race has been in any presidential election since 2008.

Arizona or Georgia in 2020 had nothing on the United States in 1880.

Six closest elections by popular vote margin (%), 1868-2020

1. 1880: Garfield defeats Hancock (+0.1)

2. 1960: Kennedy defeats Nixon (+0.2)

3. 2000: Bush defeats Gore (-0.5)

4. 1884: Cleveland defeats Blaine (+0.6)

5. 1968: Nixon defeats Humphrey (+0.7)

6. 1888: Harrison defeats Cleveland (-0.8)

Naturally, citing exact percentages from 1880 or any year in its general vicinity is an exercise in misplaced specificity. The South of that era wielded the electoral votes of millions of citizens who weren’t being permitted to vote. The nation as a whole failed to address this fact through Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment (though, to be sure, attempts were made).

The national election returns of the Gilded Age were ersatz even as they did illustrate how an electoral college functions when fed consistently close popular-vote totals. Dubious inputs produced instructive results (including two electoral inversions in the span of just four campaigns). No one understood this paradox better than the bitterly polarized Republicans and Democrats of the Gilded Age. Never before or since has the electoral college in general and winner-take-all in particular been more popular in the North.

One upstate New York newspaper captured this dynamic well in 1888. When governments in the South become democratic “in fact as well as in form,” the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle editorialized, “it may be time to adopt the popular vote plan. But as long as majorities can be rolled up in the south to order, of any size to suit any emergency, the free-voting states will cling to the electoral college as a protection against political robbery….Our forefathers did not blunder. On the contrary, it would seem that they were gifted with something like prophetic vision when they ordained the electoral college.”

Reversal margins and the extreme nature of 2020

Our method for electing presidents produces different answers to what are more commonly two wordings of the same question. Customarily, the number of votes required to reverse the outcome is identical to the margin (plus one) by which the winner prevailed.

That's not necessarily how it works in an electoral college.

Six closest elections by reversal margin (% of total popular vote to reverse outcome), 1868-2020

1. 2000: Bush defeats Gore (0.0005)

2. 1876: Hayes defeats Tilden (0.01)

3. 1884: Cleveland defeats Blaine (0.01)

4. 1916: Wilson defeats Hughes (0.02)

5. 1976: Carter defeats Ford (0.02)

6. 2020: Biden defeats Trump (0.03)

For example, in 2004 observers still attuned to 2000’s unique contours came to varying conclusions on how “close” George W. Bush’s victory over John Kerry really was. Kerry would have swung the election if he had just won Ohio. On the other hand Bush captured the Buckeye State by a relatively slim but hardly unusual margin of 2.1 percentage points. Yes, the ballots Kerry needed to reverse the overall outcome all happened to be located in just one state.

Nevertheless, that 2004 reversal margin (119,000 votes) was almost three times the size of what Republicans in 2020 would have required across three states (43,000) to force a 269-269 tie in the electoral college. In this sense 2020 was “closer” even as the Republican candidate lost the popular vote nationally by 4.4 percent and drew seven million fewer votes than the Democratic nominee. By this measure 2020 was extreme, an extremity born of chance and driven by close margins in Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin.

We think we can arrive at pretty good estimates in advance of popular vote margins, and even something like an electoral vote margin can be addressed ahead of time with probabilities. Reversal margins are different. They can land anywhere.

The election of 1968 was an instance where roughly equal numbers of voters backed each major-party candidate yet the reversal margin was relatively large. Mitt Romney’s reversal margin in 2012 was a hair smaller than Hubert Humphrey’s in 1968.

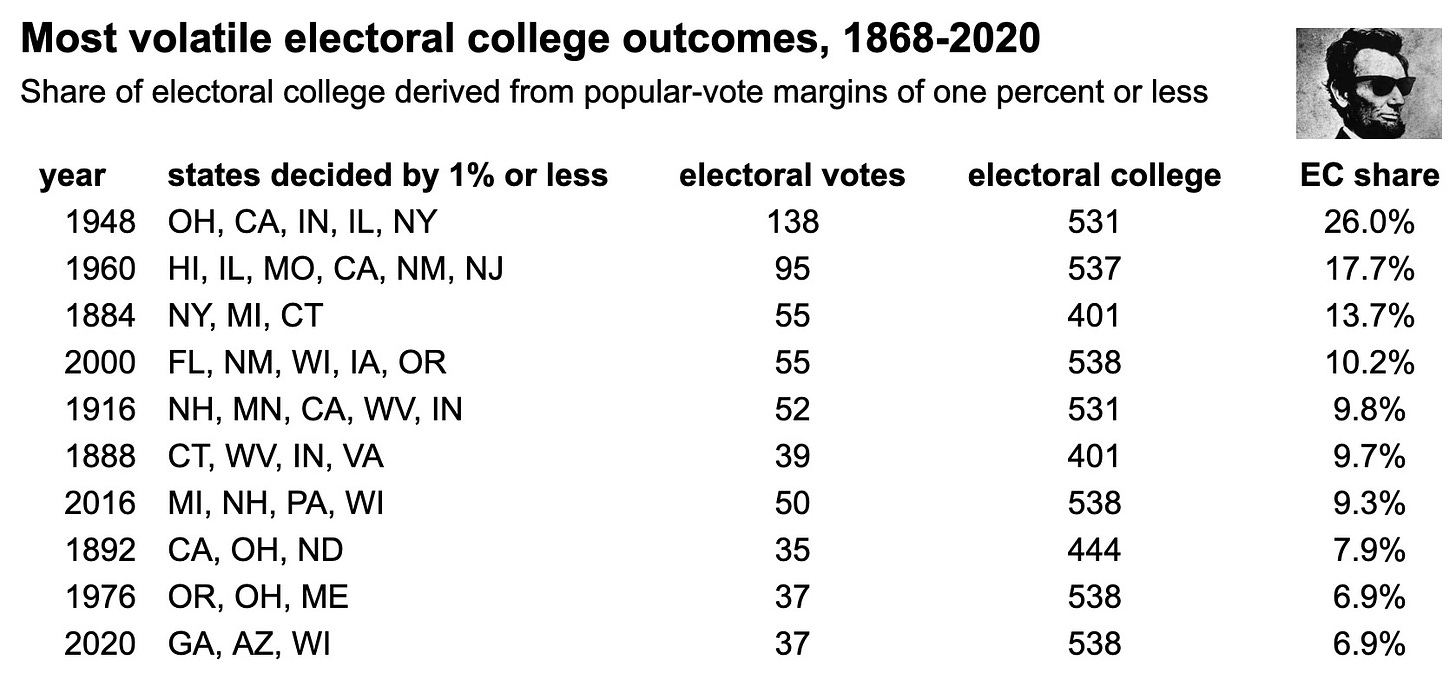

Outcome volatility and sympathy for the pollsters of 1948

In addition to all of the above measures, we may look at the returns a few days after Election Day 2024 and reflect that a very small shift in the national popular vote in either direction would have had sizable consequences in the electoral college. While this quality is partly a function of reversal margin, it also reflects something larger than the minimum swing needed to change the result.

Nate Silver recently spoke to this very quality:

{Even] a normal-sized polling error of 3 or 4 points across the board would make the Electoral College uninteresting. Harris beats her polls by that amount in every swing state, and it’s the biggest landslide since Obama in 2008 (she maybe wins Florida, too). If Trump beats his polls by that amount, it’s the worst election for Democrats in the Electoral College since 1988, though Harris might still win the popular vote.

We can refer to this as an election outcome’s volatility. It turns out that 1948, the year when the pollsters got it famously and spectacularly wrong, also ranks No. 1 by a mile for outcome volatility.

This year even if Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin (the seven expected swing states) are all decided by margins smaller than one percent, that outcome would rank behind 1948 and 1960 for volatility. To recreate a 1948 level of volatility in 2024’s electoral college, imagine behemoths like California, Texas, and Florida joining North Carolina as 50-50 tossup states.

In baseball terms, the pollsters of 1948 were perhaps the equivalent of a batter who was facing the wrong way in the batter’s box and then fell down while attempting to swing. The pollsters were bad at hitting. By chance that batter also happened to be facing the single greatest and most challenging pitcher of all time.