A brief history of women voting prior to 1920

Trailblazers cast presidential ballots decades before the 19th Amendment

The most famous instance of a woman voting in a 19th-century American presidential election dates from 1872, when 52-year-old Susan B. Anthony entered her precinct’s polling place in Rochester, New York. There she encountered a startled election worker named Jones.

“I made the remark that I didn’t think we could register her name,” Jones would later testify at Anthony’s trial. “She asked me if I was acquainted with the 14th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. I told her I was. She wanted to know if under that she was a citizen and had a right to vote.” Nonplussed, Jones stood aside as Anthony cast her ballot. She voted for President Grant.

Possibly we can see Anthony’s ballot to this day in Grant’s official total for New York, but hers was a vote cast in suffrage’s absence. Anthony challenged her disfranchisement by voting and was prosecuted for doing so. In 1873 she was found guilty and fined $100, equivalent to $2,600 today. She never paid.

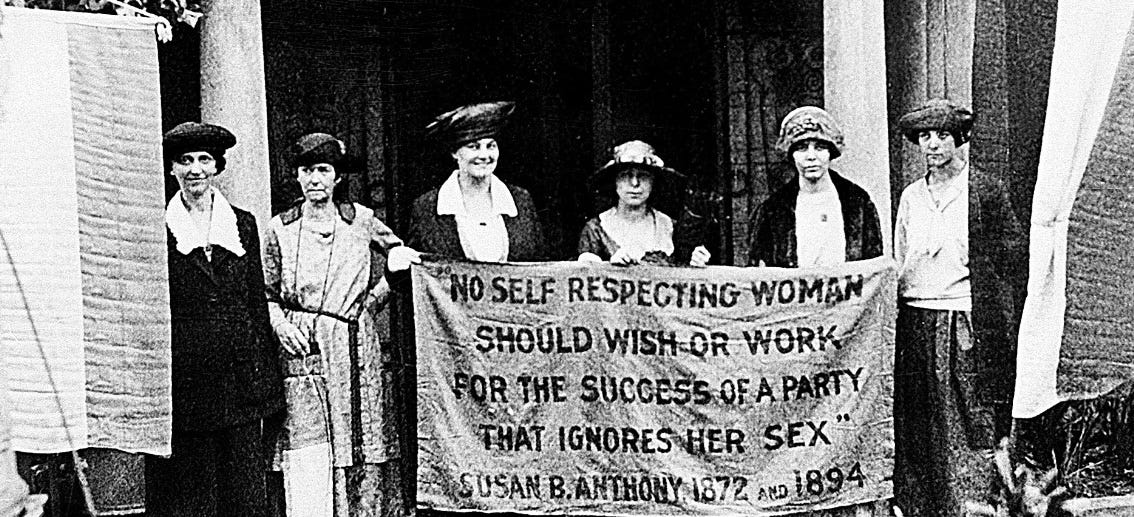

Women’s suffrage would not be enacted in the state of New York until 1917. At a celebration to commemorate the historic moment in New York City’s Cooper Union, Carrie Chapman Catt opened her remarks by addressing the crowd as “Fellow citizens.” Catt shared the stage with Anna Howard Shaw, who reminded the audience that before passing away in 1906 Anthony predicted women nationwide would be voting by 1920.

Anthony’s vision turned out to be on the money. Getting there required pulling votes out of a male population that held all the elective offices and cast all the ballots in elections. Then again by the time states were voting to ratify the 19th Amendment in 1919 and 1920, a not insignificant portion of those office holders faced electorates that already included women.

Ill-starred efforts in the South

What would become the 19th Amendment was first introduced in Congress in 1878. Suffragists were split on whether passage of the 15th Amendment in 1870 recognizing the rights of Black men to vote represented the harbinger of a future suffrage for women or a lasting preemption of their own claims. Concerned that the latter could become a self-fulfilling prophecy, a few leaders in the movement looked to the former Confederacy. If white southerners were concerned about newly enfranchised Black men, this thinking ran, perhaps the answer was enfranchising white women.

Since the end of the Civil War, former abolitionist Henry Blackwell had been mailing out pamphlets on women’s suffrage under the pointedly overt title “How the Southern States Can Make Themselves Masters of the Situation.” Blackwell was married to suffragist Lucy Stone, and by the late 1880s it appeared some southerners were of a mind to listen. In 1890 Blackwell received a long and respectful hearing from Mississippi’s white lawmakers in Washington.

For a few fateful days that August it appeared that, as part of an effort to safeguard white supremacy, a select number of married white women meeting a property qualification might gain the right to vote (by proxy through their husbands) in the Magnolia State. Proponents of Blackwell’s measure at Mississippi’s state constitutional convention noted that women were already voting in local elections in the West. For its part the state’s leading newspaper, the Jackson Clarion-Ledger, was vehemently opposed to women’s suffrage, saying the idea would make Mississippi “the laughingstock of the country.” When put to a vote, a motion to enfranchise a select number of married women in Mississippi failed 17-11.

Encouraged by this near miss, the National American Woman Suffrage Association formed a Southern Committee in 1892. Suffragist Laura Clay spoke at South Carolina’s state constitutional convention in 1895 and estimated that a $300 property requirement for women’s suffrage in the state would qualify 75,000 new white voters alongside 18,000 newly enfranchised Black women. Clay called on the delegates to give women the vote and once and for all “settle the vexed problem of white supremacy” in South Carolina. However, Clay’s measure was rejected emphatically by the delegates. With this defeat the book was effectively closed on the suffragists’ southern strategy.

In 1917 Arkansas would recognize women’s rights to vote in state and presidential primaries even as the state continued to deny that right in general elections. That partial exception notwithstanding, no state in the Deep South would enact women’s suffrage or vote in favor of the constitutional amendment’s ratification.

Mississippi did not officially ratify the 19th Amendment until 1984.

First presidential votes: November 8, 1892

In 1889, President Benjamin Harrison’s son boasted publicly that the sheer number of new western states would give Republicans an insurmountable and lasting edge in both the electoral college and in the Senate. As is often the case with political forecasts, the boast didn’t fare well in the short run.

Newly admitted Idaho actually backed Progressive Party candidate James B. Weaver over Harrison for the presidency in 1892, while fellow new state North Dakota split its three electoral votes three ways. Four years later William Jennings Bryan would sweep all but one of the “new” states for the Democrats.

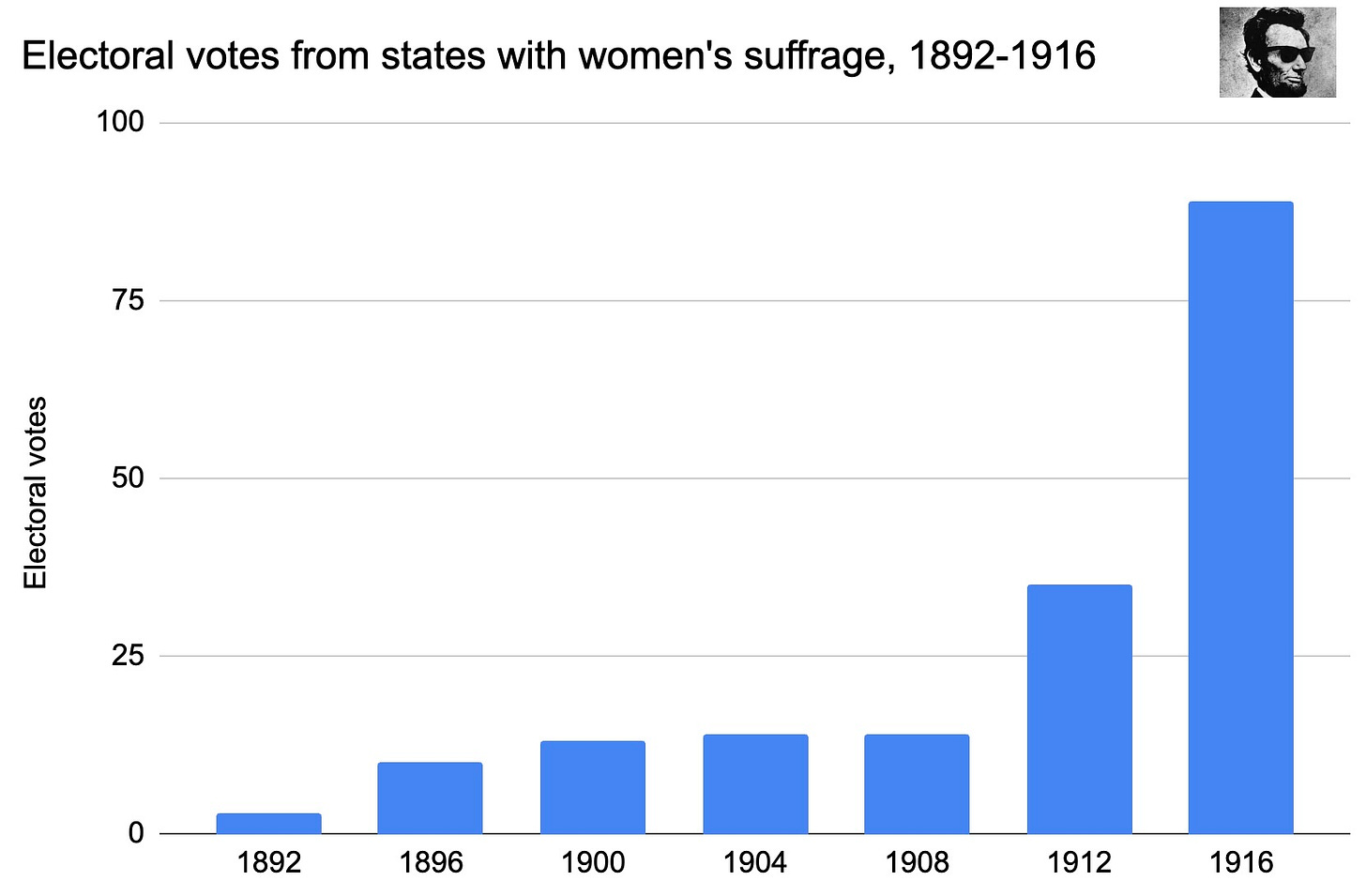

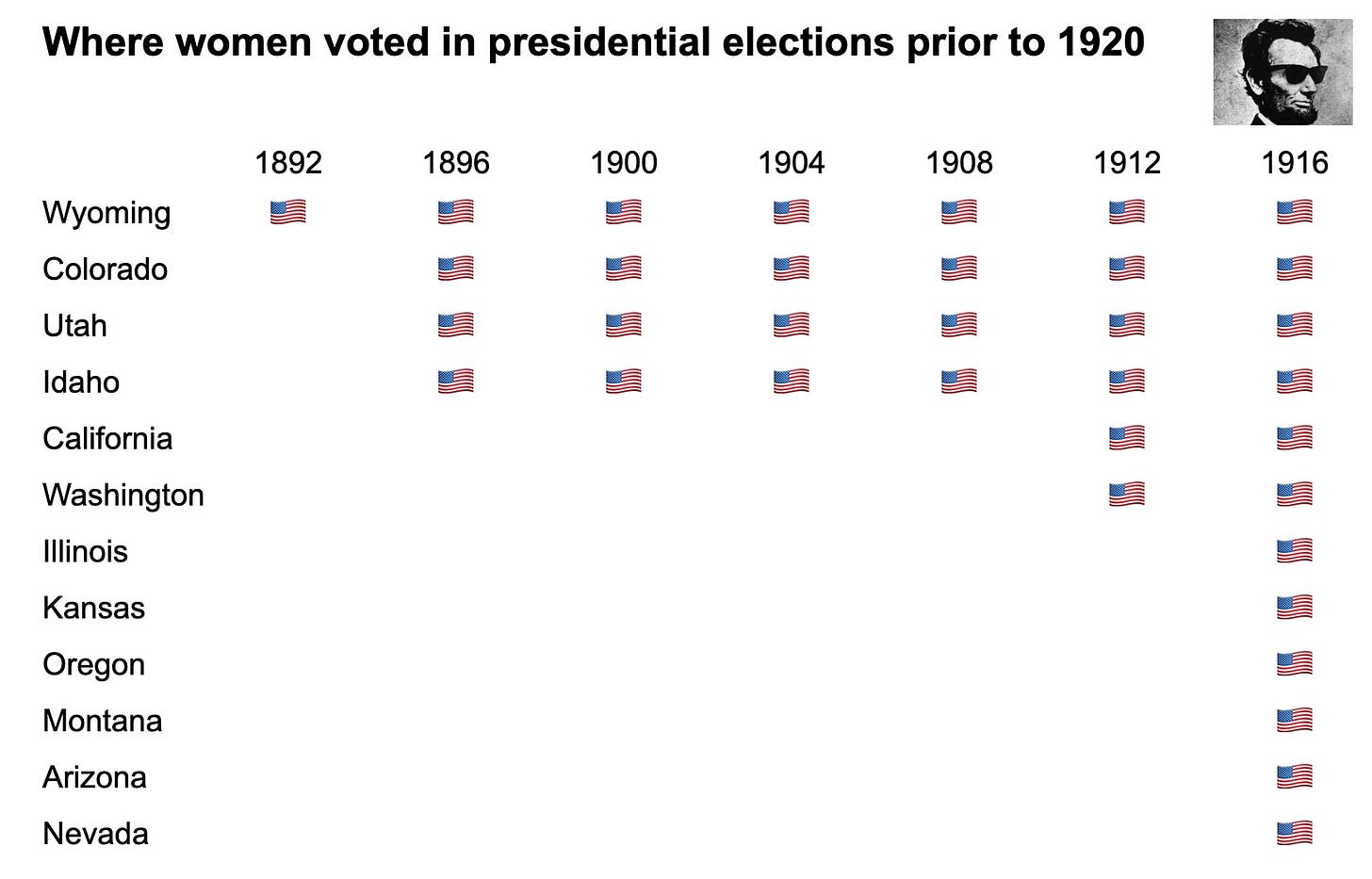

What the new states of 1889 and 1890 lacked in early support for the GOP, however, they more than made up for in women’s suffrage. Women had been voting in the Wyoming Territory since 1869. When Grover Cleveland defeated President Harrison in the election of 1892, there were perhaps 7,000 women eligible to vote in the state.

As early as December 1892, “women vote in Wyoming” became a common refrain nationally in reply to claims that expanding the suffrage would upend society or overthrow gender roles. By the time William McKinley defeated Bryan in 1896, women were voting not only in Wyoming but also in Utah, Colorado, and Idaho.

Women’s suffrage appeared to be spreading outward from the sparsely populated states of the interior West. When both houses of the California legislature approved a ballot measure that would coincide with Idaho’s referendum in 1896, suffragists anticipated their most significant victory to date. Instead, 55 percent of California’s male voters rejected the measure.

The promise of the 1890s gave way to the period that suffragists would remember as “the doldrums.” In four consecutive presidential elections from 1896 through 1908, women voted in four states and only four states.

California in 1911 and Illinois in 1913

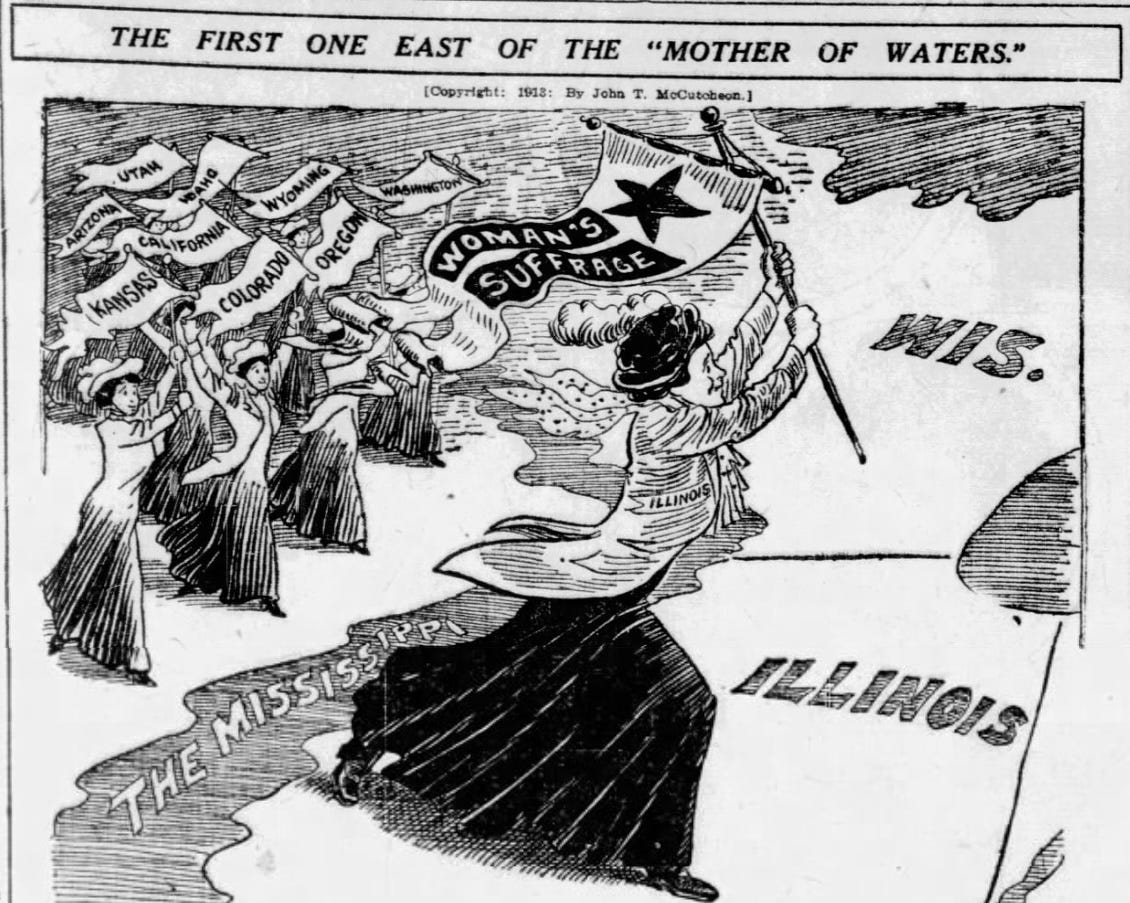

The doldrums drew to a close on November 8, 1910, when women secured the right to vote in the state of Washington. That same day four women were elected to seats in Colorado’s General Assembly.

All the while suffragists had continued organizing and campaigning in California, which alone was comparable in population in 1910 (1.5 million people) to the combined total of the five states where women were voting (1.6). The organizing and campaigning in the Golden State paid off in 1911. Proposition 4, the Women’s Suffrage Amendment, passed by just 3,500 votes out of 246,000 cast.

Innovation was the order of the day. Inventive legislative minds in Illinois put forward a suffrage bill recognizing women’s votes in any election where such balloting wasn’t already prohibited by the state constitution. These exceptions included not only most local elections but also voting for presidential electors.

In 1913 the Illinois legislature included a smattering of Progressives and Socialists in addition to the usual Republicans and Democrats. During floor debate on this limited franchise for women, a Democratic House member sought to embarrass a Progressive supporter of the measure, John M. Curran, by reading aloud a letter Curran’s wife composed in opposition to women’s suffrage. Mae Curran wrote that she was speaking for “the large, but silent, body of women who do not wish to vote and see in such a bill only a burden to themselves and a menace to the state.”

The Democratic leader of the Illinois House predicted far-reaching consequences stemming from this measure. Lee O’Neil Brown warned that the bill “is going to eliminate the Democratic party from the face of the earth. It is going to eliminate the Republican party, too.” Nevertheless, the bill passed on a close vote.

Illinois was the nation’s third-largest state in the 1910s, and its example was followed in 1914 by Montana and Nevada. By this time women were voting in Kansas, Oregon, and Arizona as well.

Women debuted as a voting demographic in presidential elections in 1892 and attained permanence in 1920. But as a discrete factor in a close national election, women truly commanded attention for the first time in 1916. This was no longer the same electoral map as in the days of Bryan, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft.

Aides to President Woodrow Wilson believed many of the old ways no longer applied to this electorate. Even the most personal of presidential matters had to be viewed in terms of what it might mean for “the women’s vote.”

The presidential election of 1916

Wilson’s wife passed away in August 1914, and in the fall of 1915 he told his adult daughters he was planning to marry Edith Bolling Galt. The president’s aides were worried about reaction from 12 states where women would vote in the following year’s election. Wilson was advised to hold off on both his wedding and especially his announcement. A grieving husband presented a more acceptable image.

The president rebuffed the advice up to a point. He and his betrothed went right ahead and announced their engagement on October 6, 1915. However, Wilson was careful to issue a separate statement as well. He announced that, as a private citizen and resident of New Jersey, he would vote that fall in favor of women’s suffrage in the Garden State.

Wilson’s one vote was not enough. The ballot measure in New Jersey went down to defeat, as did women’s suffrage initiatives in New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts all within the span of a few months in 1915. The nation’s most populous eastern states weren’t following examples set by the likes of Illinois and California. The national parties took notice of this hesitance.

While voicing unprecedented and even historic support for reform at the state level, the 1916 convention platforms were upon closer examination more (Democrats) or less (Republicans) diffident on women’s suffrage. Democrats were tip-toeing gingerly around a southern political class that was instinctively and implacably opposed to any federally directed suffrage expansion and/or (especially) enforcement. The GOP’s diffidence was less overt in its wording. Republicans did at least say they wanted “justice” for “one-half the adult people of this country.”

But in stopping short of support for a constitutional amendment, Republicans in particular made a political calculation that was curious if not baffling. Democrats as of 1916 plainly weren’t going to go that far. The election was expected to be close. It was no longer the case that women would vote in but four sparsely populated states. Now Charles Evans Hughes would seek the support of women in 12 states, including Illinois (29 electoral votes) and California (13).

Wilson won 10 of those 12 states. While Hughes did pick up the win in Illinois, the president outperformed his challenger 57 to 34 in the electoral college’s states where women voted. The conventional wisdom concluded that “He kept us out of war” was a compelling Democratic campaign theme west of the Mississippi. Senator Thomas P. Gore of Oklahoma later pronounced, “The women voters in the West elected Wilson on the peace issue.”

After the fall elections of 1916, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Rhode Island all followed the Illinois template and recognized women’s rights to vote in presidential campaigns. (In Ohio, however, that right was granted by referendum only to be revoked eight months later by the state legislature.)

The die was truly cast only when New York enacted women’s suffrage for all elections in November 1917. President Wilson promptly reversed his states’ rights stance and in January 1918 endorsed a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage as a “war measure.” Ratifying what was and is known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment in August 1920 marked the culmination of a campaign as old as the nation itself.1

Abigail Adams penned her famous “remember the ladies” letter to husband John in 1776, warning that women would “not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.” Women voted in New Jersey up to 1807, when they were disfranchised as part of a feud within that state’s Jeffersonian Republican party.